Caroli disease

| Caroli disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Congenital cystic dilatation of the intrahepatic biliar tree | |

| |

| Turbo spin echo T2-weighted axial MRI of Caroli disease, showing cystic dilatations of bile ducts (shown as white).[1][predatory publisher] | |

Caroli disease (communicating cavernous ectasia, or congenital cystic dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary tree) is a rare inherited disorder characterized by cystic dilatation (or ectasia) of the bile ducts within the liver. There are two patterns of Caroli disease: focal or simple Caroli disease consists of abnormally widened bile ducts affecting an isolated portion of liver. The second form is more diffuse, and when associated with portal hypertension and congenital hepatic fibrosis, is often referred to as "Caroli syndrome".[2] The underlying differences between the two types are not well understood. Caroli disease is also associated with liver failure and polycystic kidney disease. The disease affects about one in 1,000,000 people, with more reported cases of Caroli syndrome than of Caroli disease.[3]

Caroli disease is distinct from other diseases that cause ductal dilatation caused by obstruction, in that it is not one of the many choledochal cyst derivatives.[2]

Signs and symptoms

The first symptoms typically include fever, intermittent abdominal pain, and an enlarged liver. Occasionally, yellow discoloration of the skin occurs.[4] Caroli disease usually occurs in the presence of other diseases, such as autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, cholangitis, gallstones, biliary abscess, sepsis, liver cirrhosis, kidney failure, and cholangiocarcinoma (7% affected).[2] People with Caroli disease are 100 times more at risk for cholangiocarcinoma than the general population.[4] After recognizing symptoms of related diseases, Caroli disease can be diagnosed.[citation needed]

Morbidity is common and is caused by complications of cholangitis, sepsis, choledocholithiasis, and cholangiocarcinoma.[5] These morbid conditions often prompt the diagnosis. Portal hypertension may be present, resulting in other conditions including enlarged spleen, hematemesis, and melena.[6] These problems can severely affect the patient's quality of life. In a 10-year period between 1995 and 2005, only 10 patients were surgically treated for Caroli disease, with an average patient age of 45.8 years.[5]

After reviewing 46 cases of Caroli disease before 1990, 21.7% of the cases were the result of an intraheptic cyst or nonobstructive biliary tree dilation, 34.7% were linked with congenital hepatic fibrosis, 13% were isolated choledochal cystic dilation, and the remaining 24.6% had a combination of all three.[7]

Causes

The cause appears to be genetic; the simple form is an autosomal dominant trait, while the complex form is an autosomal recessive trait.[2] Females are more prone to Caroli disease than males.[8] Family history may include kidney and liver disease due to the link between Caroli disease and ARPKD.[6] PKHD1, the gene linked to ARPKD, has been found mutated in patients with Caroli syndrome. PKHD1 is expressed primarily in the kidneys with lower levels in the liver, pancreas, and lungs, a pattern consistent with phenotype of the disease, which primarily affects the liver and kidneys.[2][6] The genetic basis for the difference between Caroli disease and Caroli syndrome has not been defined.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

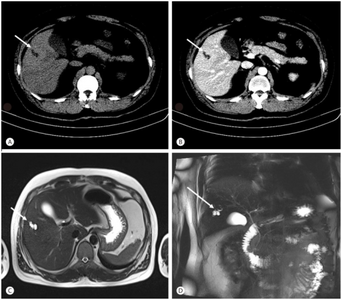

Modern imaging techniques allow the diagnosis to be made more easily and without invasive imaging of the biliary tree.[9] Commonly, the disease is limited to the left lobe of the liver. Images taken by CT scan, X-ray, or MRI show enlarged intrahepatic (in the liver) bile ducts due to ectasia. Using an ultrasound, tubular dilation of the bile ducts can be seen. On a CT scan, Caroli disease can be observed by noting the many fluid-filled, tubular structures extending to the liver.[4] A high-contrast CT must be used to distinguish the difference between stones and widened ducts. Bowel gas and digestive habits make it difficult to obtain a clear sonogram, so a CT scan is a good substitution. When the intrahepatic bile duct wall has protrusions, it is clearly seen as central dots or a linear streak.[10] Caroli disease is commonly diagnosed after this “central dot sign” is detected on a CT scan or ultrasound.[10] However, cholangiography is the best, and final, approach to show the enlarged bile ducts as a result of Caroli disease.[citation needed]

-

Bileduct dilatation in segment 5 arrow a,b) CT, c) MRI, d) MRCP

-

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) of Caroli disease, showing cystic dilatations of bile ducts.[1]

Treatment

The treatment depends on clinical features and the location of the biliary abnormality. When the disease is localized to one hepatic lobe, hepatectomy relieves symptoms and appears to remove the risk of malignancy.[11] Good evidence suggests that malignancy complicates Caroli disease in roughly 7% of cases.[11]

Antibiotics are used to treat the inflammation of the bile duct, and ursodeoxycholic acid is used for hepatolithiasis.[9] Ursodiol is given to treat cholelithiasis. In diffuse cases of Caroli disease, treatment options include conservative or endoscopic therapy, internal biliary bypass procedures, and liver transplantation in carefully selected cases.[11] Surgical resection has been used successfully in patients with monolobar disease.[9] An orthotopic liver transplant is another option, used only when antibiotics have no effect, in combination with recurring cholangitis. With a liver transplant, cholangiocarcinoma is usually avoided in the long run.[12]

Family studies are necessary to determine if Caroli disease is due to inheritable causes. Regular follow-ups, including ultrasounds and liver biopsies, are performed.[citation needed]

Prognosis

Mortality is indirect and caused by complications. After cholangitis occurs, patients typically die within 5–10 years.[3]

Epidemiology

Caroli disease is typically found in Asia, and diagnosed in persons under the age of 22. Cases have also been found in infants and adults. As medical imaging technology improves, diagnostic age decreases.[citation needed]

History

Jacques Caroli, a gastroenterologist, first described a rare congenital condition in 1958 in Paris, France.[8][13] He described it as "nonobstructive saccular or fusiform multifocal segmental dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts"; basically, he observed cavernous ectasia in the biliary tree causing a chronic, often life-threatening hepatobiliary disease. [14] Caroli, born in France in 1902, learned and practiced medicine in Angers. After World War II, he was chief of service for 30 years at Saint-Antoine in Paris. Before dying in 1979, he was honored with the rank of commander in the Legion of Honour in 1976.[13]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Maurea S, Mollica C, Imbriaco M, Fusari M, Camera L, Salvatore M (2010). "Magnetic Resonance Cholangiography with Mangafodipir Trisodium in Caroli's Disease with Pancreas Involvement". Journal of the Pancreas. 11 (5): 460–3. PMID 20818116. Archived from the original on 2021-05-26. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Karim B (August 2007). "Caroli's Disease Case Reports" (PDF). Indian Pediatrics. 41 (8): 848–50. PMID 15347876. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Romano WJ: Caroli Disease at eMedicine

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Carolis disease". Medcyclopaedia. GE. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lendoire J, Schelotto PB, Rodríguez JA, et al. (2007). "Bile duct cyst type V (Caroli's disease): surgical strategy and results". HPB (Oxford). 9 (4): 281–4. doi:10.1080/13651820701329258. PMC 2215397. PMID 18345305.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Friedman JR: Caroli Disease at eMedicine

- ↑ Choi BI, Yeon KM, Kim SH, Han MC (January 1990). "Caroli disease: central dot sign in CT". Radiology. 174 (1): 161–3. doi:10.1148/radiology.174.1.2294544. PMID 2294544.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kahn, Charles E, Jr. January 2003. Collaborative Hypertext of Radiology. Medical College of Wisconsin. Archived September 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Ananthakrishnan AN, Saeian K (April 2007). "Caroli's disease: identification and treatment strategy". Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 9 (2): 151–5. doi:10.1007/s11894-007-0010-7. PMID 17418061. S2CID 28595781.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Chiba T, Shinozaki M, Kato S, Goto N, Fujimoto H, Kondo F (March 2002). "Caroli's disease: central dot sign re-examined by CT arteriography and CT during arterial portography". Eur Radiol. 12 (3): 701–2. doi:10.1007/s003300101048. PMID 11870491. S2CID 26652277.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Taylor AC, Palmer KR (February 1998). "Caroli's disease". Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 10 (2): 105–8. doi:10.1097/00042737-199802000-00001. PMID 9581983. S2CID 11622337.

- ↑ Ulrich F, Steinmüller T, Settmacher U, et al. (September 2002). "Therapy of Caroli's disease by orthotopic liver transplantation". Transplant. Proc. 34 (6): 2279–80. doi:10.1016/S0041-1345(02)03235-9. PMID 12270398.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Jacques Caroli at Who Named It?

- ↑ Miller WJ, Sechtin AG, Campbell WL, Pieters PC (1 August 1995). "Imaging findings in Caroli's disease". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 165 (2): 333–7. doi:10.2214/ajr.165.2.7618550. PMID 7618550. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with sources from predatory publications

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2021

- Ciliopathy

- Hepatology

- Rare diseases

- Syndromes affecting the hepatobiliary system

- Syndromes with tumors

![Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) of Caroli disease, showing cystic dilatations of bile ducts.[1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4d/MRCP_of_Caroli_disease.jpg/344px-MRCP_of_Caroli_disease.jpg)