Captopril

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈkæptəprɪl/ |

| Trade names | Capoten, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | ACE inhibitor[1] |

| Main uses | High blood pressure, heart failure, diabetic kidney disease, heart attack[2] |

| Side effects | Difficulty sleeping, stomach ulcers[3] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Typical dose | 6.25 to 75 mg BID[4] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682823 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 70–75% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 2.2 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H15NO3S |

| Molar mass | 217.28 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Captopril, sold under the brand name Capoten among others, is a medication used to treat high blood pressure, heart failure, diabetic kidney disease, and for a short time after a heart attack.[2] For high blood pressure it is one of a number of first line options.[2] It is taken by mouth as a liquid or tablet.[3] It may not work as well in Black people.[2]

Common side effects include difficulty sleeping and stomach ulcers.[3] Other side effects may include decreased appetite, flushing, tiredness, change in taste, high potassium, and Raynaud's, where fingers and toes turn white and blue.[3][2] Use in pregnancy or breastfeeding may harm the baby.[3][2] It is an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and works by inhibiting the renin–angiotensin system.[1]

Captopril was patented in 1976 and approved for medical use in 1980.[6] It is available as a generic medication.[4] In the United Kingdom a dose of between 12.5 to 50 mg twice per day costs the NHS less than £2 as of 2021.[4] In the United States this amount costs about 35 USD.[7]

Medical uses

Captopril's main uses are based on its vasodilation and inhibition of some renal function activities. These benefits are most clearly seen in: 1) Hypertension 2) Cardiac conditions such as congestive heart failure and after myocardial infarction 3) Preservation of kidney function in diabetic nephropathy.

Additionally, it has shown mood-elevating properties in some patients. This is consistent with the observation that animal screening models indicate putative antidepressant activity for this compound, although one study has been negative. Formal clinical trials in depressed patients have not been reported.[8]

It has also been investigated for use in the treatment of cancer.[9] Captopril stereoisomers were also reported to inhibit some metallo-β-lactamases.[10]

Dosage

For high blood pressure it is generally started at 12.5 to 25 mg twice per day and may be increased up to 75 mg twice per day.[4] For high blood pressure, the first dose is typically taken at bedtime.[3]

Side effects

Side effects of captopril include cough due to increase in the plasma levels of bradykinin, angioedema, agranulocytosis, proteinuria, hyperkalemia, taste alteration, teratogenicity, postural hypotension, acute renal failure, and leukopenia.[11]

Rare side effects include a low blood count or low sugar, heart atack, depression, large breasts, and kidney or liver problems.[3]

Captopril is avoided if there has been a previous allergic reaction to any other ACE inhibitor.[3]

Except for postural hypotension, which occurs due to the short and fast mode of action of captopril, most of the side effects mentioned are common for all ACE inhibitors. Among these, cough is the most common adverse effect. Hyperkalemia can occur, especially if used with other drugs which elevate potassium level in blood, such as potassium-sparing diuretics. Other side effects are:

- Itching

- Headache

- Tachycardia

- Chest pain

- Palpitations

- Dysgeusia

- Weakness

The adverse drug reaction (ADR) profile of captopril is similar to other ACE inhibitors, with cough being the most common ADR.[12] However, captopril is also commonly associated with rash and taste disturbances (metallic or loss of taste), which are attributed to the unique thiol moiety.[13]

Interactions

It can interact with several other medicines, but severe effects can result with aliskiren, allopurinol, azathioprine, everolimus and lithium.[3]

Overdose

ACE inhibitor overdose can be treated with naloxone.[14][15]

Mechanism

Captopril blocks the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II and prevents the degradation of vasodilatory prostaglandins, thereby inhibiting vasoconstriction and promoting systemic vasodilation.[17]

Pharmacokinetics

Unlike the majority of ACE inhibitors, captopril is not administered as a prodrug (the only other being lisinopril).[18] About 70% of orally administered captopril is absorbed. Bioavailability is reduced by presence of food in stomach. It is partly metabolised and partly excreted unchanged in urine.[19]

Captopril also has a relatively poor pharmacokinetic profile. The short half-life necessitates two or three times per day dosing, which may reduce patient compliance.

Captopril has a half life of 2.2 hours.[1] It has a duration of action of 12-24 hours.

Chemistry

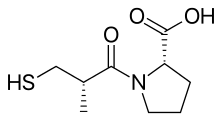

Captopril has an L-proline group which allows for it to be more bioavailable within oral formulations. The thiol moiety within the molecule has been associated with two significance adverse effects: the hapten or immune response commonly seen as a skin rash as well as dysgeusia, or metallic mouth.

Synthesis

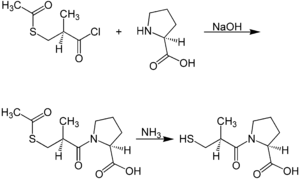

A chemical synthesis of captopril by treatment of L-proline with (2S)-3-acetylthio-2-methylpropanoyl chloride under basic conditions (NaOH), followed by aminolysis of the protective acetyl group to unmask the drug's free thiol, is depicted in the figure at right.[20]

| Captopril synthesis 1 | Captopril synthesis 2 |

|---|---|

|

|

Procedure 2 taken out of patent US4105776. See examples 28, 29a and 36.

History

In the late 1960s, John Vane of the Royal College of Surgeons of England was working on mechanisms by which the body regulates blood pressure.[25] He was joined by Sérgio Henrique Ferreira of Brazil, who had been studying the venom of a Brazilian pit viper, the jararaca (Bothrops jararaca), and brought a sample of the viper's venom. Vane's team found that one of the venom's peptides selectively inhibited the action of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), which was thought to function in blood pressure regulation; the snake venom functions by severely depressing blood pressure. During the 1970s, ACE was found to elevate blood pressure by controlling the release of water and salts from the kidneys.

Captopril, an analog of the snake venom's ACE-inhibiting peptide, was first synthesized in 1975 by three researchers at the U.S. drug company E.R. Squibb & Sons Pharmaceuticals (now Bristol-Myers Squibb): Miguel Ondetti, Bernard Rubin, and David Cushman. Squibb filed for U.S. patent protection on the drug in February 1976, U.S. Patent 4,046,889 was granted in September 1977, and captopril was approved for medical use in 1980.[6] It was the first ACE inhibitor developed and was considered a breakthrough both because of its mechanism of action and also because of the development process.[26][27] In the 1980s, Vane received the Nobel prize and was knighted for his work and Ferreira received the National Order of Scientific Merit from Brazil.

The development of captopril was among the earliest successes of the revolutionary concept of ligand-based drug design. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system had been extensively studied in the mid-20th century, and this system presented several opportune targets in the development of novel treatments for hypertension. The first two targets that were attempted were renin and ACE. Captopril was the culmination of efforts by Squibb's laboratories to develop an ACE inhibitor.

Ondetti, Cushman, and colleagues built on work that had been done in the 1960s by a team of researchers led by John Vane at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. The first breakthrough was made by Kevin K.F. Ng[28][29][30] in 1967, when he found the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II took place in the pulmonary circulation instead of in the plasma. In contrast, Sergio Ferreira[31] found bradykinin disappeared in its passage through the pulmonary circulation. The conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II and the inactivation of bradykinin were thought to be mediated by the same enzyme.

In 1970, using bradykinin potentiating factor (BPF) provided by Sergio Ferreira,[32] Ng and Vane found the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II was inhibited during its passage through the pulmonary circulation. BPF was later found to be a peptide in the venom of a lancehead viper (Bothrops jararaca), which was a “collected-product inhibitor” of the converting enzyme. Captopril was developed from this peptide after it was found via QSAR-based modification that the terminal sulfhydryl moiety of the peptide provided a high potency of ACE inhibition.[33]

Captopril gained FDA approval on April 6, 1981. The drug became a generic medicine in the U.S. in February 1996, when the market exclusivity held by Bristol-Myers Squibb for captopril expired.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Benowitz, Neal L. (2020). "11. Antihypertensive agents". In Katzung, Bertram G.; Trevor, Anthony J. (eds.). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 183–185. ISBN 978-1-260-45231-0. Archived from the original on 2021-10-10. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "Captopril Monograph for Professionals - Drugs.com". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 "2. Cardiovascular system". British National Formulary (BNF) (82 ed.). London: BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2021 – March 2022. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-85711-413-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 BNF 81: March-September 2021. BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. 2021. p. 182. ISBN 978-0857114105.

- ↑ List of nationally authorised medicinal products Archived 2021-10-31 at the Wayback Machine. European Medicines Agency. 26 November 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 467. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-10-15.

- ↑ "Captopril Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ↑ Murphy DL, Mitchell PB, Potter WZ. "Novel Pharmacological Approaches to the Treatment of Depression". Archived from the original on May 12, 2008.

- ↑ Attoub S, Gaben AM, Al-Salam S, Al Sultan MA, John A, Nicholls MG, et al. (September 2008). "Captopril as a potential inhibitor of lung tumor growth and metastasis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1138 (1): 65–72. Bibcode:2008NYASA1138...65A. doi:10.1196/annals.1414.011. PMID 18837885. S2CID 24210204.

- ↑ Brem J, van Berkel SS, Zollman D, Lee SY, Gileadi O, McHugh PJ, et al. (January 2016). "Structural Basis of Metallo-β-Lactamase Inhibition by Captopril Stereoisomers". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 60 (1): 142–50. doi:10.1128/AAC.01335-15. PMC 4704194. PMID 26482303.

- ↑ "Captopril (ACE inhibitor): side effects". lifehugger. 2008-07-09. Archived from the original on 2009-08-14. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- ↑ Rossi S, ed. (2006). Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook.

- ↑ Atkinson AB, Robertson JI (October 1979). "Captopril in the treatment of clinical hypertension and cardiac failure". Lancet. 2 (8147): 836–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(79)92186-X. PMID 90928. S2CID 32209360.

- ↑ Nelson L, Howland MA, Lewin NA, Smith SW, Goldfrank R, Hoffman RS, Flomenbaum N (2019). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 953. ISBN 978-1-259-85961-8.

- ↑ Smith, Silas W. (2010). "Drugs and pharmaceuticals: management of intoxication and antidotes". In Luch, Andreas (ed.). Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology: Volume 2: Clinical Toxicology. Vol. 2. Basel: Springer. ISBN 978-3-7643-8337-4. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- ↑ Akif M, Georgiadis D, Mahajan A, Dive V, Sturrock ED, Isaac RE, Acharya KR (July 2010). "High-resolution crystal structures of Drosophila melanogaster angiotensin-converting enzyme in complex with novel inhibitors and antihypertensive drugs". Journal of Molecular Biology. 400 (3): 502–17. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.024. PMID 20488190.

- ↑ Vallerand AH, Sanoski CA, Deglin JH (2014-06-05). Davis's drug guide for nurses (Fourteenth ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 978-0-8036-4085-6. OCLC 881473728.

- ↑ Brown NJ, Vaughan DE (April 1998). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors". Circulation. 97 (14): 1411–20. doi:10.1161/01.cir.97.14.1411. PMID 9577953.

- ↑ Duchin KL, McKinstry DN, Cohen AI, Migdalof BH (April 1988). "Pharmacokinetics of captopril in healthy subjects and in patients with cardiovascular diseases". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 14 (4): 241–59. doi:10.2165/00003088-198814040-00002. PMID 3292102. S2CID 46614471.

- ↑ Shimazaki M, Hasegawa J, Kan K, Nomura K, Nose Y, Kondo H, Ohashi T, Watanabe K (1982). "Synthesis of captopril starting from an optically active .BETA.-hydroxy acid". Chem. Pharm. Bull. 30 (9): 3139–3146. doi:10.1248/cpb.30.3139.

- ↑ M. A. Ondetti, D. W. Cushman, DE 2703828; eidem, U.S. Patent 4,046,889 and U.S. Patent 4,105,776 (1977, 1977, 1978 all to Squibb).

- ↑ Ondetti MA, Rubin B, Cushman DW (April 1977). "Design of specific inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme: new class of orally active antihypertensive agents". Science. 196 (4288): 441–4. Bibcode:1977Sci...196..441O. doi:10.1126/science.191908. PMID 191908.

- ↑ Cushman DW, Cheung HS, Sabo EF, Ondetti MA (December 1977). "Design of potent competitive inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Carboxyalkanoyl and mercaptoalkanoyl amino acids". Biochemistry. 16 (25): 5484–91. doi:10.1021/bi00644a014. PMID 200262.

- ↑ Nam DH, Lee CS, Ryu DD (December 1984). "An improved synthesis of captopril". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 73 (12): 1843–4. doi:10.1002/jps.2600731251. PMID 6396401.

- ↑ Crow, James Mitchell. "Drugs with bite: The healing powers of venoms". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 2016-04-13. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ Bryan J (2009). "From snake venom to ACE inhibitor the discovery and rise of captopril". Pharmaceutical Journal. Archived from the original on 2015-01-26. Retrieved 2015-01-08.

- ↑ Blankley CJ (September 1985). "Chronicals of Drug Discovery, vol. 2". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 74 (9): 1029–30. doi:10.1002/jps.2600740942.

- ↑ Ng KK, Vane JR (November 1967). "Conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II". Nature. 216 (5117): 762–6. Bibcode:1967Natur.216..762N. doi:10.1038/216762a0. PMID 4294626. S2CID 4289093.

- ↑ Ng KK, Vane JR (April 1968). "Fate of angiotensin I in the circulation". Nature. 218 (5137): 144–50. Bibcode:1968Natur.218..144N. doi:10.1038/218144a0. PMID 4296306. S2CID 4174541.

- ↑ Ng KK, Vane JR (March 1970). "Some properties of angiotensin converting enzyme in the lung in vivo". Nature. 225 (5238): 1142–4. Bibcode:1970Natur.225.1142N. doi:10.1038/2251142b0. PMID 4313869. S2CID 4200012.

- ↑ Ferreira SH, Vane JR (June 1967). "The disappearance of bradykinin and eledoisin in the circulation and vascular beds of the cat". British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. 30 (2): 417–24. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1967.tb02148.x. PMC 1557274. PMID 6036419.

- ↑ Smith CG, Vane JR (May 2003). "The discovery of captopril". FASEB Journal. 17 (8): 788–9. doi:10.1096/fj.03-0093life. PMID 12724335. S2CID 45232683.

- ↑ Patlak M (March 2004). "From viper's venom to drug design: treating hypertension". FASEB Journal. 18 (3): 421. doi:10.1096/fj.03-1398bkt. PMID 15003987. S2CID 1045315.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- U.S. Patent 4,046,889 Archived 2019-05-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: date format

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- ACE inhibitors

- Carboxamides

- Carboxylic acids

- Enantiopure drugs

- Pyrrolidines

- Thiols

- Bristol-Myers Squibb

- Daiichi Sankyo

- RTT