Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome

| Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: BRBNS, or Blue rubber bleb syndrome, or Blue rubber-bleb nevus or Bean syndrome | |

| |

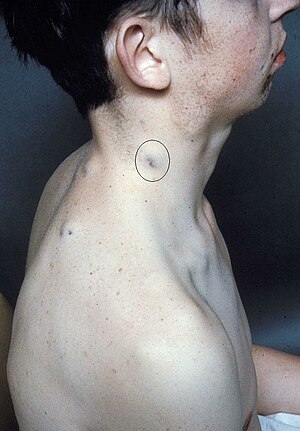

| The cutaneous vascular malformations of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome | |

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome is a rare disorder that consists mainly of abnormal blood vessels affecting the skin or internal organs – usually the gastrointestinal tract.[1] The disease is characterized by the presence of fluid-filled blisters (blebs) as visible, circumscribed, chronic lesions (nevus).

BRBNS is caused by somatic mutations in the TEK (TIE2) gene.[2]

It was described by William Bennett Bean in 1958.[3]

Signs and symptoms

BRBNS is a venous malformation,[4] formerly, though incorrectly, thought to be related to the hemangioma. It carries significant potential for serious bleeding.[5] Lesions are most commonly found on the skin and in the small intestine and distal large bowel. Other organs with the lesions can also be found on the central nervous system, liver, and muscles.[6] It usually presents soon after birth or during early infancy.[6][7]

Causes

The cause as to why blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome occurs is currently unknown. The syndrome is considered sporadic. Someone who is diagnosed with BRBNS likely has a family relative that has other multifocal venous malformations[8] which is a symptom of the disease. Autosomal inheritance of BRBNS has been found in familial cases associated with chromosome 9p, but the majority of cases are sporadic.[6] The disease correlates with an onset of GI complications. It is reported that GI bleeding is the most common cause of death in most cases.[9]

Diagnosis

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome is difficult to diagnose because of how rare the disease is. Diagnosing BRBNS is usually based on the presence of cutaneous lesions with or without gastrointestinal bleeding and/or involvement of other organs.[6] Cutaneous angiomas are found on the surface of the skin and from the scalp to the soles of feet.[6] The characteristics of the cutaneous lesions are rubbery, soft, tender and hemorrhagic, easily compressible and promptly refill after compression.[6] A physical examination is mostly used to diagnosis cutaneous angiomas on the surface of the skin. Endoscopy has been the leading diagnostic tool for diagnosing BRBNS for those who suffer from lesions in the gastrointestinal tract. The GI tract is illuminated and visualized in endoscopy. [8] Endoscopy also allows immediate therapeutic measures like argon plasma, coagulation, laser photocoagulation, sclerotherapy, or band ligation.[10] Besides physical examination and endoscopy, ultrasonography, radiographic images, CT and magnetic resonance imaging are helpful for detection of affected visceral organs.[6]

Treatment

There are several methods to treat BRBNS as it is not a curable disease. Treatment for BRBNS depends on the severity and location of affected areas.[11] The cutaneous lesions can be effectively treated by laser, surgical removal, electrodesiccation, cryotherapy, and sclerotherapy.[12] In other cases, iron therapy (such as iron supplementation) and blood transfusions are used to conservatively manage BRBNS because of the amount of blood that is lost from the GI bleeding.[8] It is not necessary to remove the lesions in the gastrointestinal system unless the bleeding leads to anemia and repeatedly have blood transfusions.[8] It is safe to remove GI lesions surgically, but one or more lengthy operations may be required.[8] If there is a recurrence with new angioma in the gastrointestinal tract, laser-steroid therapy is needed.[13] Treatment is not required for those with skin spots, but some individuals with BRBNS may want treatment for cosmetic reasons or if the affected location causes discomfort or affects normal function.[11]

Incidence

Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome affects males and females in equal numbers.[8] According to a review of literature, 20% of patients with BRBNS were from the United States, 15% from Japan, 9% from Spain, 9% from Germany, 6% from China, and 6% from France; and a lower number of cases from other countries.[6] This indicates that any race can be affected by BRBNS.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ↑ Baigrie, Dana; Rice, Ashley S.; An, In C. (2022). "Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31082129. Archived from the original on 2022-03-27. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

- ↑ Soblet J, Kangas J, Nätynki M, Mendola A, Helaers R, Uebelhoer M, et al. (January 2017). "Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus (BRBN) Syndrome Is Caused by Somatic TEK (TIE2) Mutations". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 137 (1): 207–216. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2016.07.034. PMID 27519652.

- ↑ Mulliken, John B. (2013). "13. Capillary malformations, hyperkeratotic stains, telangiectasias, and miscellaneous vascular blots". In Mulliken, John B.; Burrows, Patricia E.; Fishman, Steven J. (eds.). Mulliken and Young's Vascular Anomalies: Hemangiomas and Malformations (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 552. ISBN 978-0-19-972254-9. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ↑ Dobru D, Seuchea N, Dorin M, Careianu V (September 2004). "Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: case report and literature review". Romanian Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (3): 237–40. PMID 15470538. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ Ertem D, Acar Y, Kotiloglu E, Yucelten D, Pehlivanoglu E (February 2001). "Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome". Pediatrics. 107 (2): 418–20. doi:10.1542/peds.107.2.418. PMID 11158481. Archived from the original on 2019-12-13. Retrieved 2022-01-27.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Jin XL, Wang ZH, Xiao XB, Huang LS, Zhao XY (December 2014). "Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: a case report and literature review". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (45): 17254–9. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17254. PMC 4258599. PMID 25493043.

- ↑ Kassarjian A, Fishman SJ, Fox VL, Burrows PE (October 2003). "Imaging characteristics of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 181 (4): 1041–8. doi:10.2214/ajr.181.4.1811041. PMID 14500226.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 "Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus syndrome - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders)". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ↑ "Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (Bean syndrome)". www.dermatologyadvisor.com. Archived from the original on 2018-10-08. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ↑ Agnese M, Cipolletta L, Bianco MA, Quitadamo P, Miele E, Staiano A (April 2010). "Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome". Acta Paediatrica. 99 (4): 632–5. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01608.x. PMID 19958301. S2CID 5722981.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-03-20. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ↑ Chen W, Chen H, Shan G, Yang M, Hu F, Li Q, Chen L, Xu G (August 2017). "Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: our experience and new endoscopic management". Medicine. 96 (33): e7792. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000007792. PMC 5571702. PMID 28816965.

- ↑ Deng ZH, Xu CD, Chen SN (February 2008). "Diagnosis and treatment of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome in children". World Journal of Pediatrics. 4 (1): 70–3. doi:10.1007/s12519-008-0015-9. PMID 18402258. S2CID 42702922.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Blue rubber bleb nevus; Bean syndrome at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases