Thiamine deficiency

| Thiamine deficiency[1] | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Beriberi, vitamin B1 deficiency, thiamine-deficiency syndrome[1][2] | |

| |

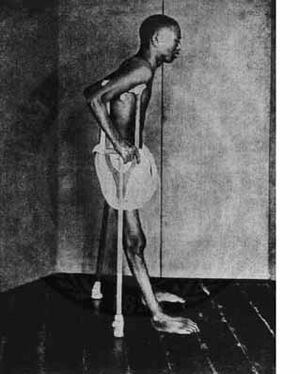

| A person with beriberi during the early twentieth century in Southeast Asia | |

| Specialty | Neurology, cardiology, pediatrics |

| Symptoms | |

| Types | Wet, dry, gastrointestinal[3] |

| Causes | Not enough thiamine[1] |

| Risk factors | Diet of mostly white rice; alcoholism, dialysis, chronic diarrhea, diuretics[1][4] |

| Prevention | Food fortification[1] |

| Treatment | Thiamine supplementation[1] |

| Frequency | Rare (US)[1] |

Thiamine deficiency is a medical condition of low levels of thiamine (vitamin B1).[1] A severe and chronic form is known as beriberi.[1][5] There are two main types in adults: wet beriberi, and dry beriberi.[1] Wet beriberi affects the cardiovascular system resulting in a fast heart rate, shortness of breath, and leg swelling.[1] Dry beriberi affects the nervous system resulting in numbness of the hands and feet, confusion, trouble moving the legs, and pain.[1] A form with loss of appetite and constipation may also occur.[3] Another type, acute beriberi, is found mostly in babies and presents with loss of appetite, vomiting, lactic acidosis, changes in heart rate, and enlargement of the heart.[6]

Risk factors include a diet of mostly white rice, as well as alcoholism, dialysis, chronic diarrhea, and taking high doses of diuretics.[1][4] Rarely it may be due to a genetic condition that results in difficulties absorbing thiamine found in food.[1] Wernicke encephalopathy and Korsakoff syndrome are forms of dry beriberi.[4] Diagnosis is based on symptoms, low levels of thiamine in the urine, high blood lactate, and improvement with treatment.[7]

Treatment is by thiamine supplementation, either by mouth or by injection.[1] With treatment, symptoms generally resolve in a couple of weeks.[7] The disease may be prevented at the population level through the fortification of food.[1]

Thiamine deficiency is rare in the United States.[8] It remains relatively common in sub-Saharan Africa.[2] Outbreaks have been seen in refugee camps.[4] Thiamine deficiency has been described for thousands of years in Asia and became more common in the late 1800s with the increased processing of rice.[9]

Signs and symptoms

Beriberi

Symptoms of beriberi include weight loss, emotional disturbances, impaired sensory perception, weakness and pain in the limbs, and periods of irregular heart rate. Edema (swelling of bodily tissues) is common. It may increase the amount of lactic acid and pyruvic acid within the blood. In advanced cases, the disease may cause high-output cardiac failure and death.

Symptoms may occur concurrently with those of Wernicke's encephalopathy, a primarily neurological thiamine-deficiency related condition.

Beriberi is divided into four categories as follows. The first three are historical and the fourth, gastrointestinal beriberi, was recognized in 2004:

- Dry beriberi especially affects the peripheral nervous system.

- Wet beriberi especially affects the cardiovascular system and other bodily systems.

- Infantile beriberi affects the babies of malnourished mothers.

- Gastrointestinal beriberi affects the digestive system and other bodily systems.

Dry beriberi

Dry beriberi causes wasting and partial paralysis resulting from damaged peripheral nerves. It is also referred to as endemic neuritis. It is characterized by:

- Difficulty in walking

- Tingling or loss of sensation (numbness) in hands and feet

- Loss of tendon reflexes[10]

- Loss of muscle function or paralysis of the lower legs

- Mental confusion/speech difficulties

- Pain

- Involuntary eye movements (nystagmus)

- Vomiting

A selective impairment of the large proprioceptive sensory fibers without motor impairment can occur and present as a prominent sensory ataxia, which is a loss of balance and coordination due to loss of the proprioceptive inputs from the periphery and loss of position sense.[11]

Brain disease

Wernicke's encephalopathy (WE), Korsakoff syndrome (alcohol amnestic disorder), Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome are forms of dry beriberi.[4]

Wernicke's encephalopathy is the most frequently encountered manifestation of thiamine deficiency in Western society,[12][13] though it may also occur in patients with impaired nutrition from other causes, such as gastrointestinal disease,[12] those with HIV/AIDS, and with the injudicious administration of parenteral glucose or hyperalimentation without adequate B-vitamin supplementation.[14] This is a striking neuro-psychiatric disorder characterized by paralysis of eye movements, abnormal stance and gait, and markedly deranged mental function.[15]

Korsakoff syndrome is, in general, considered to occur with deterioration of brain function in patients initially diagnosed with WE.[16] This is an amnestic-confabulatory syndrome characterized by retrograde and anterograde amnesia, impairment of conceptual functions, and decreased spontaneity and initiative.[17]

Alcoholics may have thiamine deficiency because of the following:

- Inadequate nutritional intake: Alcoholics tend to intake less than the recommended amount of thiamine.

- Decreased uptake of thiamine from the GI tract: Active transport of thiamine into enterocytes is disturbed during acute alcohol exposure.

- Liver thiamine stores are reduced due to hepatic steatosis or fibrosis.[18]

- Impaired thiamine utilization: Magnesium, which is required for the binding of thiamine to thiamine-using enzymes within the cell, is also deficient due to chronic alcohol consumption. The inefficient utilization of any thiamine that does reach the cells will further exacerbate the thiamine deficiency.

- Ethanol per se inhibits thiamine transport in the gastrointestinal system and blocks phosphorylation of thiamine to its cofactor form (ThDP).[19]

Following improved nutrition and the removal of alcohol consumption, some impairments linked with thiamine deficiency are reversed, in particular poor brain functionality, although in more severe cases, Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome leaves permanent damage. (See delirium tremens.)

Wet beriberi

Wet beriberi affects the heart and circulatory system. It is sometimes fatal, as it causes a combination of heart failure and weakening of the capillary walls, which causes the peripheral tissues to become edematous. Wet beriberi is characterized by:

- Increased heart rate

- Vasodilation leading to decreased systemic vascular resistance, and high output heart failure[20]

- Elevated jugular venous pressure[21]

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath) on exertion

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- Peripheral edema[21] (swelling of lower legs)

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

Gastrointestinal beriberi

Gastrointestinal beriberi causes abdominal pain. Gastrointestinal beriberi is characterized by:

Infants

Infantile beriberi usually occurs between two and six months of age in children whose mothers have inadequate thiamine intake. It may present as either wet or dry beriberi.[2]

In the acute form, the baby develops dyspnea and cyanosis and soon dies of heart failure. These symptoms may be described in infantile beriberi:

- Hoarseness, where the child makes moves to moan but emits no sound or just faint moans[24] caused by nerve paralysis[10]

- Weight loss, becoming thinner and then marasmic as the disease progresses[24]

- Vomiting[24]

- Diarrhea[24]

- Pale skin[10]

- Edema[10][24]

- Ill temper[10]

- Alterations of the cardiovascular system, especially tachycardia (rapid heart rate)[10]

- Convulsions occasionally observed in the terminal stages[24]

Cause

Beriberi may also be caused by shortcomings other than inadequate intake: diseases or operations on the digestive tract, alcoholism,[21] dialysis, genetic deficiencies, etc. All these causes mainly affect the central nervous system, and provoke the development of what is known as Wernicke's disease or Wernicke's encephalopathy.

Wernicke's disease is one of the most prevalent neurological or neuropsychiatric diseases.[25] In autopsy series, features of Wernicke lesions are observed in approximately 2% of general cases.[26] Medical record research shows that about 85% had not been diagnosed, although only 19% would be asymptomatic. In children, only 58% were diagnosed. In alcohol abusers, autopsy series showed neurological damages at rates of 12.5% or more. Mortality caused by Wernicke's disease reaches 17% of diseases, which means 3.4/1000 or about 25 million contemporaries.[27][28] The number of people with Wernicke's disease may be even higher, considering that early stages may have dysfunctions prior to the production of observable lesions at necropsy. In addition, uncounted numbers of people can experience fetal damage and subsequent diseases.

Genetics

Genetic diseases of thiamine transport are rare but serious. Thiamine responsive megaloblastic anemia (TRMA) with diabetes mellitus and sensorineural deafness[29] is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the gene SLC19A2,[30] a high affinity thiamine transporter. TRMA patients do not show signs of systemic thiamine deficiency, suggesting redundancy in the thiamine transport system. This has led to the discovery of a second high-affinity thiamine transporter, SLC19A3.[31][32] Leigh disease (subacute necrotising encephalomyelopathy) is an inherited disorder that affects mostly infants in the first years of life and is invariably fatal. Pathological similarities between Leigh disease and WE led to the hypothesis that the cause was a defect in thiamine metabolism. One of the most consistent findings has been an abnormality of the activation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex.[33]

Mutations in the SLC19A3 gene have been linked to biotin-thiamine responsive basal ganglia disease,[34] which is treated with pharmacological doses of thiamine and biotin, another B vitamin.

Other disorders in which a putative role for thiamine has been implicated include subacute necrotising encephalomyelopathy, opsoclonic cerebellopathy (a paraneoplastic syndrome), and Nigerian seasonal ataxia. In addition, several inherited disorders of ThDP-dependent enzymes have been reported,[35] which may respond to thiamine treatment.[17]

Pathophysiology

Thiamine in the human body has a half-life of 18 days and is quickly exhausted, particularly when metabolic demands exceed intake. A derivative of thiamine, thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), is a cofactor involved in the citric acid cycle, as well as connecting the breakdown of sugars with the citric acid cycle. The citric acid cycle is a central metabolic pathway involved in the regulation of carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid metabolism, and its disruption due to thiamine deficiency inhibits the production of many molecules including the neurotransmitters glutamic acid and GABA.[36] Additionally thiamine may also be directly involved in neuromodulation.[37]

Diagnosis

A positive diagnosis test for thiamine deficiency involves measuring the activity of the enzyme transketolase in erythrocytes (Erythrocyte transketolase activation assay). Alternatively, thiamine and its phosphphosphorylated derivatives, can directly be detected in whole blood, tissues, foods, animal feed, and pharmaceutical preparations following the conversion of thiamine to fluorescent thiochrome derivatives (Thiochrome assay) and separation by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).[38][39][40] Capillary electrophoresis (CE) techniques and in-capillary enzyme reaction methods have emerged as alternative techniques in quantifying and monitoring thiamine levels in samples.[41] The normal thiamine concentration in EDTA-blood is about 20-100 µg/l.

Treatment

Many people with beriberi can be treated with thiamine alone.[42] Given thiamine intravenously (and later orally), rapid and dramatic[21] recovery occurs, generally within 24 hours.[43]

Improvements of peripheral neuropathy may require several months of thiamine treatment.[44]

Epidemiology

Beriberi is a recurrent nutritional disease in detention houses, even in this century. In 1999, an outbreak of beriberi occurred in a detention center in Taiwan.[45] High rates of illness and death in overcrowded Haitian jails in 2007 were traced to the traditional practice of washing rice before cooking.[46] In the Ivory Coast, among a group of prisoners with heavy punishment, 64% were affected by beriberi. Before beginning treatment, prisoners exhibited symptoms of dry or wet beriberi with neurological signs (tingling: 41%), cardiovascular signs (dyspnoea: 42%, thoracic pain: 35%), and edemas of the lower limbs (51%). With treatment the rate of healing was about 97%.[47]

Populations under extreme stress may be at higher risk for beriberi. Displaced populations, such as refugees from war, are susceptible to micronutritional deficiency, including beriberi.[48] The severe nutritional deprivation caused by famine also can cause beriberis, although symptoms may be overlooked in clinical assessment or masked by other famine-related problems.[49] An extreme weight-loss diet can, rarely, induce a famine-like state and the accompanying beriberi.[21]

History

Earliest written descriptions of thiamine deficiency are from Ancient China in the context of chinese medicine. One of the earliest is by Ge Hong in his book Zhou hou bei ji fang (Emergency Formulas to Keep up Your Sleeve) written sometime during the 3rd century. Hong called the illness by the name jiao qi, which can be interpreted as "foot qi". He described the symptoms to include swelling, weakness and numbness of the feet. He also acknowledged that the illness could be deadly, and claimed that it could be cured by eating certain foods such as fermented soybeans in wine. Better known examples of early descriptions of "foot qi" are by Chao Yuanfang (who lived during 550–630) in his book Zhu bing yuan hou lun (Sources and Symptoms of All Diseases)[50][51] and by Sun Simiao (581–682) in his book Bei ji qian jin yao fang (Essential Emergency Formulas Worth a Thousand in Gold).[52][51][53][54]

In the late 19th century, beriberi was studied by Takaki Kanehiro, a British-trained Japanese medical doctor of the Imperial Japanese Navy.[55] Beriberi was a serious problem in the Japanese navy: Sailors fell ill an average of four times a year in the period 1878 to 1881, and 35% were cases of beriberi.[55] In 1883, Takaki learned of a very high incidence of beriberi among cadets on a training mission from Japan to Hawaii, via New Zealand and South America. The voyage lasted more than nine months and resulted in 169 cases of sickness and 25 deaths on a ship of 376 men. With the support of the Japanese Navy, he conducted an experiment in which another ship was deployed on the same route, except that its crew was fed a diet of meat, fish, barley, rice, and beans. At the end of the voyage, this crew had only 14 cases of beriberi and no deaths. This convinced Takaki and the Japanese Navy that diet was the cause.[55] In 1884, Takaki observed that beriberi was common among low-ranking crew who were often provided free rice and thus ate little else, but not among crews of Western navies, nor among Japanese officers who consumed a more varied diet.

In 1897, Christiaan Eijkman, a Dutch physician and pathologist, demonstrated that beriberi is caused by poor diet, and discovered that feeding unpolished rice (instead of the polished variety) to chickens helped to prevent beriberi. The following year, Sir Frederick Hopkins postulated that some foods contained "accessory factors"—in addition to proteins, carbohydrates, fats, and salt—that were necessary for the functions of the human body.[56][57] In 1901, Gerrit Grijns, a Dutch physician and assistant to Christiaan Eijkman in the Netherlands, correctly interpreted beriberi as a deficiency syndrome,[58] and between 1910 and 1913, Edward Bright Vedder established that an extract of rice bran is a treatment for beriberi.[citation needed] In 1929, Eijkman and Hopkins were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries.

Etymology

Although according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term "beriberi" comes from a Sinhalese phrase meaning "weak, weak" or "I cannot, I cannot", the word being duplicated for emphasis,[59] the origin of the phrase is questionable. It has also been suggested to come from Hindi, Arabic and a few other languages, with many meanings like "weakness", "sailor" and even "sheep". Such suggested origins were listed by Heinrich Botho Scheube among others. Edward Vedder wrote in his book Beriberi (1913) that "it is impossible to definitely trace the origin of the word beriberi". Word berbere was used in writing at least as early as 1568 by Diogo do Couto, when he described the deficiency in India.[60]

"Kakke", which is a Japanese synonym for thiamine deficiency, comes from the way "jiao qi" is pronounced in Japanese.[61] "Jiao qi" is an old word used in Chinese medicine to describe beriberi.[50] "Kakke" is supposed to have entered into the Japanese language sometime between the 6th and 8th centuries.[61]

Other animals

Poultry

As most feedstuffs used in poultry diets contain enough quantities of vitamins to meet the requirements in this species, deficiencies in this vitamin do not occur with commercial diets. This was, at least, the opinion in the 1960s.[62]

Mature chickens show signs three weeks after being fed a deficient diet. In young chicks, it can appear before two weeks of age. Onset is sudden in young chicks. There is anorexia and an unsteady gait. Later on, there are locomotor signs, beginning with an apparent paralysis of the flexor of the toes. The characteristic position is called "stargazing", meaning a chick "sitting on its hocks and the head in opisthotonos".

Response to administration of the vitamin is rather quick, occurring a few hours later.[63][64]

Ruminants

Polioencephalomalacia (PEM) is the most common thiamine deficiency disorder in young ruminant and nonruminant animals. Symptoms of PEM include a profuse, but transient, diarrhea, listlessness, circling movements, star gazing or opisthotonus (head drawn back over neck), and muscle tremors.[65] The most common cause is high-carbohydrate feeds, leading to the overgrowth of thiaminase-producing bacteria, but dietary ingestion of thiaminase (e.g., in bracken fern), or inhibition of thiamine absorption by high sulfur intake are also possible.[66] Another cause of PEM is Clostridium sporogenes or Bacillus aneurinolyticus infection. These bacteria produce thiaminases that will cause an acute thiamine deficiency in the affected animal.[67]

Snakes

Snakes that consume a diet largely composed of goldfish and feeder minnows are susceptible to developing thiamine deficiency. This is often a problem observed in captivity when keeping garter and ribbon snakes that are fed a goldfish-exclusive diet, as these fish contain thiaminase, an enzyme that breaks down thiamine.[68]

Wild birds and fish

Thiamine deficiency has been identified as the cause of a paralytic disease affecting wild birds in the Baltic Sea area dating back to 1982.[69] In this condition, there is difficulty in keeping the wings folded along the side of the body when resting, loss of the ability to fly and voice, with eventual paralysis of the wings and legs and death. It affects primarily 0.5–1 kg sized birds such as the herring gull (Larus argentatus), common starling (Sturnus vulgaris) and common eider (Somateria mollissima). Researches noted, "Because the investigated species occupy a wide range of ecological niches and positions in the food web, we are open to the possibility that other animal classes may suffer from thiamine deficiency as well."[69]p. 12006

In the counties of Blekinge and Skåne (southernmost Sweden), mass deaths of several bird species, especially the European herring gull, have been observed since the early 2000s. More recently, species of other classes seems to be affected. High mortality of salmon (Salmo salar) in the river Mörrumsån is reported, and mammals such as the Eurasian Elk (Alces alces) have died in unusually high numbers. Lack of thiamine is the common denominator where analysis is done. In April 2012, the County Administrative Board of Blekinge found the situation so alarming that they asked the Swedish government to set up a closer investigation.[70]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 "Beriberi". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. 2015. Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Adamolekun, B; Hiffler, L (24 October 2017). "A diagnosis and treatment gap for thiamine deficiency disorders in sub-Saharan Africa?". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1408 (1): 15–19. Bibcode:2017NYASA1408...15A. doi:10.1111/nyas.13509. PMID 29064578.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ferri, Fred F. (2017). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1368. ISBN 9780323529570. Archived from the original on 2017-11-11.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Nutrition and Growth Guidelines | Domestic Guidelines - Immigrant and Refugee Health". CDC. March 2012. Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ Hermann, Wolfgang; Obeid, Rima (2011). Vitamins in the prevention of human diseases. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 58. ISBN 9783110214482.

- ↑ Gropper, Sareen S. and Smith, Jack L. (2013). Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (6 ed.). Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 324. ISBN 978-1133104056.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 Swaiman, Kenneth F.; Ashwal, Stephen; Ferriero, Donna M.; Schor, Nina F.; Finkel, Richard S.; Gropman, Andrea L.; Pearl, Phillip L.; Shevell, Michael (2017). Swaiman's Pediatric Neurology E-Book: Principles and Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. e929. ISBN 9780323374811. Archived from the original on 2017-11-11.

- ↑ "Thiamin Fact Sheet for Consumers". Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS): USA.gov. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ↑ Lanska, DJ (2010). Chapter 30: historical aspects of the major neurological vitamin deficiency disorders: the water-soluble B vitamins. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 95. pp. 445–76. doi:10.1016/S0072-9752(08)02130-1. ISBN 9780444520098. PMID 19892133.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Katsura, E.; Oiso, T. (1976). Beaton, G.H.; Bengoa, J.M. (eds.). "Chapter 9. Beriberi" (PDF). World Health Organization Monograph Series No. 62: Nutrition in Preventive Medicine. Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-08.

- ↑ Spinazzi, Marco; Angelini, Corrado; Patrini, Cesare (2010). "Subacute sensory ataxia and optic neuropathy with thiamine deficiency". Nature Reviews Neurology. 6 (5): 288–93. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2010.16. PMID 20308997.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Kril JJ (1996). "Neuropathology of thiamine deficiency disorders". Metab Brain Dis. 11 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1007/BF02080928. PMID 8815394.

- ↑ For an interesting discussion on thiamine fortification of foods, specifically targetting beer, see "Wernicke's encephalopathy and thiamine fortification of food: time for a new direction?". Medical Journal of Australia. Archived from the original on 2011-08-31.

- ↑ Butterworth RF, Gaudreau C, Vincelette J, et al. (1991). "Thiamine deficiency and wernicke's encephalopathy in AIDS". Metab Brain Dis. 6 (4): 207–12. doi:10.1007/BF00996920. PMID 1812394.

- ↑ Harper C. (1979). "Wernicke's encephalopathy, a more common disease than realised (a neuropathological study of 51 cases)". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 42 (3): 226–231. doi:10.1136/jnnp.42.3.226. PMC 490724. PMID 438830.

- ↑ McCollum EV A History of Nutrition. Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press, Houghton Mifflin; 1957.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Butterworth RF. Thiamin. In: Shils ME, Shike M, Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins RJ, editors. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease, 10th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

- ↑ Butterworth RF (1993). "Pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for the reversible (thiamine-responsive) and irreversible (thiamine non-responsive) neurological symptoms of Wernicke's encephalopathy". Drug Alcohol Rev. 12 (3): 315–22. doi:10.1080/09595239300185371. PMID 16840290.

- ↑ Rindi G, Imarisio L, Patrini C (1986). "Effects of acute and chronic ethanol administration on regional thiamin pyrophosphokinase activity of the rat brain". Biochem Pharmacol. 35 (22): 3903–8. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(86)90002-X. PMID 3022743.

- ↑ Anand, I. S.; Florea, V. G. (2001). "High Output Cardiac Failure". Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 3 (2): 151–159. doi:10.1007/s11936-001-0070-1. PMID 11242561.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 McIntyre, Neil; Stanley, Nigel N. (1971). "Cardiac Beriberi: Two Modes of Presentation". BMJ. 3 (5774): 567–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.3.5774.567. PMC 1798841. PMID 5571454.

- ↑ Donnino M (2004). "Gastrointestinal Beriberi: A Previously Unrecognized Syndrome". Ann Intern Med. 141 (11): 898–899. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00035. PMID 15583247.

- ↑ Duca, J., Lum, C., & Lo, A. (2015). Elevated Lactate Secondary to Gastrointestinal Beriberi. J GEN INTERN MED Journal of General Internal Medicine

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 Latham, Michael C. (1997). "Chapter 16. Beriberi and thiamine deficiency". Human nutrition in the developing world (Food and Nutrition Series – No. 29). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). ISSN 1014-3181. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03.

- ↑ Cernicchiaro, Luis (2007), Enfermedad de Wernicke (o Encefalopatía de Wernicke). Monitoring an acute and recovered case for twelve years. [Wernicke´s Disease (or Wernicke´s Encephalopathy)] (in Spanish), archived from the original on 2013-05-22

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Salen, Philip N (1 March 2013). Kulkarni, Rick (ed.). "Wernicke Encephalopathy". Medscape. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013.

- ↑ Harper, CG; Giles, M; Finlay-Jones, R (April 1986). "Clinical signs in the Wernicke-Korsakoff complex: a retrospective analysis of 131 cases diagnosed at necropsy". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 49 (4): 341–5. doi:10.1136/jnnp.49.4.341. PMC 1028756. PMID 3701343.

- ↑ Harper, C (March 1979). "Wernicke's encephalopathy: a more common disease than realised. A neuropathological study of 51 cases". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 42 (3): 226–31. doi:10.1136/jnnp.42.3.226. PMC 490724. PMID 438830.

- ↑ Slater, PV (1978). "Thiamine Responsive Megaloblastic Anemia with severe diabetes mellitus and sensorineural deafness (TRMA)". The Australian Nurses' Journal. 7 (11): 40–3. PMID 249270.

- ↑ Kopriva, V; Bilkovic, R; Licko, T (Dec 1977). "Tumours of the small intestine (author's transl)". Ceskoslovenska Gastroenterologie a Vyziva. 31 (8): 549–53. ISSN 0009-0565. PMID 603941.

- ↑ Beissel, J (Dec 1977). "The role of right catheterization in valvular prosthesis surveillance (author's transl)". Annales de Cardiologie et d'Angéiologie. 26 (6): 587–9. ISSN 0003-3928. PMID 606152.

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 249270

- ↑ Butterworth RF. Pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency disorders. In: McCandless DW, ed. Cerebral Energy Metabolism and Metabolic Encephalopathy. Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1985.

- ↑ Biotin-Thiamine-Responsive Basal Ganglia Disease - GeneReviews® - NCBI Bookshelf Archived 2018-05-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Blass JP. Inborn errors of pyruvate metabolism. In: Stanbury JB, Wyngaarden JB, Frederckson DS et al., eds. Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983.

- ↑ Sechi, G; Serra, A (May 2007). "Wernicke's encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management". Lancet Neurology. 6 (5): 442–55. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70104-7. PMID 17434099.

- ↑ Hirsch, JA; Parrott, J (2012). "New considerations on the neuromodulatory role of thiamine". Pharmacology. 89 (1–2): 111–6. doi:10.1159/000336339. PMID 22398704.

- ↑ Bettendorff, L; Peeters, M.; Jouan, C.; Wins, P.; Schoffeniels, E. (1991). "Determination of thiamin and its phosphate esters in cultured neurons and astrocytes using an ion-pair reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatographic method". Anal. Biochem. 198 (1): 52–59. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(91)90505-N. PMID 1789432.

- ↑ Losa, R; Sierra, MI; Fernández, A; Blanco, D; Buesa, JM. (2005). "Determination of thiamine and its phosphorylated forms in human plasma, erythrocytes and urine by HPLC and fluorescence detection: a preliminary study on cancer patients". J Pharm Biomed Anal. 37 (5): 1025–1029. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2004.08.038. PMID 15862682.

- ↑ Lu, J; Frank, EL. (May 2008). "Rapid HPLC measurement of thiamine and its phosphate esters in whole blood". Clin. Chem. 54 (5): 901–906. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2007.099077. PMID 18356241.

- ↑ Shabangi, M; Sutton, JA. (2005). "Separation of thiamin and its phosphate esters by capillary zone electrophoresis and its application to the analysis of water-soluble vitamins". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 38 (1): 66–71. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2004.11.061. PMID 15907621.

- ↑ Nguyen-Khoa, Dieu-Thu Beriberi (Thiamine Deficiency) Treatment & Management Archived 2014-03-24 at the Wayback Machine. Mescape

- ↑ Tanphaichitr V. Thiamin. In: Shils ME, Olsen JA, Shike M et al., editors. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 9th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999

- ↑ Maurice V, Adams RD, Collins GH. The Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome and Related Neurologic Disorders Due to Alcoholism and Malnutrition. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1989.

- ↑ Chen KT, Twu SJ, Chiou ST, Pan WH, Chang HJ, Serdula MK (2003). "Outbreak of beriberi among illegal mainland Chinese immigrants at a detention center in Taiwan". Public Health Rep. 118 (1): 59–64. doi:10.1093/phr/118.1.59. PMC 1497506. PMID 12604765.

- ↑ Sprague, Jeb; Alexandra, Eunida (17 January 2007). "Haiti: Mysterious Prison Ailment Traced to U.S. Rice". Inter Press Service. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013.

- ↑ Aké-Tano, O.; Konan, E. Y.; Tetchi, E. O.; Ekou, F. K.; Ekra, D.; Coulibaly, A.; Dagnan, N. S. (2011). "Le béribéri, maladie nutritionnelle récurrente en milieu carcéral en Côte-d'Ivoire". Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique. 104 (5): 347–351. doi:10.1007/s13149-011-0136-6. PMID 21336653.

- ↑ Prinzo, Z. Weise; de Benoist, B. (2009). "Meeting the challenges of micronutrient deficiencies in emergency-affected populations" (PDF). Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 61 (2): 251–7. doi:10.1079/PNS2002151. PMID 12133207. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-19.

- ↑ Golden, Mike (May 1997). "Diagnosing Beriberi in Emergency Situations". Field Exchange (1): 18. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 HA Smith, p. 26-28

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Benedict, CA (2018-10-25). "Forgotten Disease: Illnesses Transformed in Chinese Medicine by Hilary A. Smith (review)". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 92 (3): 550–551. doi:10.1353/bhm.2018.0059. ISSN 1086-3176.

- ↑ HA Smith, p. 44

- ↑ "TCM history V the Sui & Tang Dynasties". Archived from the original on 2017-07-14. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- ↑ "Sun Simiao: Author of the Earliest Chinese Encyclopedia for Clinical Practice". Archived from the original on 2007-07-04. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Itokawa, Yoshinori (1976). "Kanehiro Takaki (1849–1920): A Biographical Sketch". Journal of Nutrition. 106 (5): 581–8. doi:10.1093/jn/106.5.581. PMID 772183.

- ↑ Challem, Jack (1997). "The Past, Present and Future of Vitamins". Archived from the original on 8 June 2010.[unreliable medical source?]

- ↑ Christiaan Eijkman, Beriberi and Vitamin B1, Nobelprize.org, Nobel Media AB, archived from the original on 17 January 2010, retrieved 8 July 2013

- ↑ Grijns, G. (1901). "Over polyneuritis gallinarum". Geneeskundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch-Indie. 43: 3–110.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary: "Beri-beri ... a Cingalese word, f. beri weakness, the reduplication being intensive ...", page 203, 1937

- ↑ HA Smith, p. 118-119

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 HA Smith, p. 149

- ↑ Merck Veterinary Manual, ed 1967, pp 1440-1441.

- ↑ R.E. Austic and M.L. Scott, Nutritional deficiency diseases, in Diseases of poultry, ed. by M.S. Hofstad, Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, USA ISBN 0-8138-0430-2, p. 50.

- ↑ The disease is described more carefully here: merckvetmanual.com Archived 2008-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ National Research Council. 1996. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, Seventh Revised Ed. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- ↑ Polioencephalomalacia: Introduction Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Merck Veterinary Manual

- ↑ Polioencephalomacia: Introduction Archived 2010-05-28 at the Wayback Machine, "ACES Publications"

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-09-13. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ 69.0 69.1 Balk, L; Hägerroth, PA; Akerman, G; Hanson, M; Tjärnlund, U; Hansson, T; Hallgrimsson, GT; Zebühr, Y; Broman, D; Mörner, T.; Sundberg, H.; et al. (2009). "Wild birds of declining European species are dying from a thiamine deficiency syndrome". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106 (29): 12001–12006. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10612001B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0902903106. PMC 2715476. PMID 19597145.

- ↑ Blekinge län, Länsstyrelsen (2013). "2012-04-15 500-1380-13 Förhöjd dödlighet hos fågel, lax og älg" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-02.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Cited sources

- HA Smith (2017). Forgotten disease: illnesses transformed in Chinese medicine. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jry029. ISBN 9781503603509. OCLC 993877848.

External links

- "BERI-BERI". The Encyclopaedia Britannica; A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. Vol. III (AUSTRIA LOWER to BISECTRIX ) (11th ed.). Cambridge, England and New York: At the University Press. 1910. pp. 774–775. Retrieved 23 October 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ARNOLD D (2010). "British India and the beri-beri problem". Medical History. 54 (3): 295–314. doi:10.1017/S0025727300004622. PMC 2889456. PMID 20592882.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- Webarchive template wayback links

- All articles lacking reliable references

- Articles lacking reliable references from July 2012

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2012

- CS1: long volume value

- Reduplicants

- Vitamin deficiencies

- Thiamine

- RTT