Bed bug

| Bed bugs | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Cimicosis, bed bug bites, bedbugs, bed bug infestation | |

| |

| An adult bed bug (Cimex lectularius) with the typical flattened oval shape | |

| Specialty | Family medicine, dermatology |

| Symptoms | None to prominent blisters, itchy[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Minutes to days after the bite[2] |

| Causes | Cimex (primarily Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus)[3] |

| Risk factors | Travel, second-hand furnishings[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on finding bed bugs and symptoms[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Allergic reaction, scabies, dermatitis herpetiformis[2] |

| Treatment | Symptomatic, bed bug eradication[2] |

| Medication | Antihistamines, corticosteroids[2] |

| Frequency | Relatively common[6] |

Bed bugs are a type of insect that feed on human blood, usually at night.[7] Their bites can result in a number of health impacts including skin rashes, psychological effects, and allergic symptoms.[5] Bed bug bites may lead to skin changes ranging from invisible to small areas of redness to prominent blisters.[1][2] Symptoms may take between minutes to days to appear and itchiness is generally present.[2] Some individuals may feel tired or have a fever.[2] Typically, uncovered areas of the body are affected and often three bites occur in a row.[2] Bed bugs bites are not known to transmit any infectious disease.[5][7] Complications may rarely include areas of dead skin or vasculitis.[2]

Bed bug bites are caused primarily by two species of insects of the Cimex type: Cimex lectularius (the common bed bug) and Cimex hemipterus, primarily in the tropics.[3] Their size ranges between 1 and 7 mm.[7] They spread by crawling between nearby locations or by being carried within personal items.[2] Infestation is rarely due to a lack of hygiene but is more common in high-density areas.[2][8] Diagnosis involves both finding the bugs and the occurrence of compatible symptoms.[5] Bed bugs spend much of their time in dark, hidden locations like mattress seams or cracks in a wall.[2]

Treatment is directed towards the symptoms.[2] Eliminating bed bugs from the home is often difficult, partly because bed bugs can survive up to a year without feeding.[2] Repeated treatments of a home may be required.[2] These treatments may include heating the room to 50 °C (122 °F) for more than 90 minutes, frequent vacuuming, washing clothing at high temperatures, and the use of various pesticides.[2]

Bed bugs occur in all regions of the globe.[7] Rates of infestations are relatively common, following an increase since the 1990s.[3][4][6] The exact causes of this increase are unclear; theories including increased human travel, more frequent exchange of second-hand furnishings, a greater focus on control of other pests, and increasing resistance to pesticides.[4] Bed bugs have been known human parasites for thousands of years.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Skin

Individual responses to bites vary, ranging from no visible effect (in about 20–70%),[3][5] to small flat (macular) spots, to the formation of prominent blisters (wheals and bullae) along with intense itching that may last several days.[5] Vesicles and nodules may also form. The bites often occur in a line. A central spot of bleeding may also occur due to the release of blood thinning substances in the bug's saliva.[4]

Symptoms may not appear until some days after the bites have occurred.[5] Reactions often become more brisk after multiple bites due to possible sensitization to the salivary proteins of the bed bug.[3] The skin reaction usually occurs in the area of the bite which is most commonly the arms, shoulders and legs as they are more frequently exposed at night.[5] Numerous bites may lead to a red rash or hives.[5]

-

Bedbug bites

-

Bedbug bites

-

Bedbug bites

-

Bedbug bites

Psychological

Serious infestations and chronic attacks can cause anxiety, stress, and sleep difficulties.[5] Development of refractory delusional parasitosis is possible, as a person develops an overwhelming obsession with bed bugs.[9]

Other

A number of other symptoms may occur from either the bite of the bed bugs or from their exposure. Serious allergic reactions including anaphylaxis from the injection of serum and other nonspecific proteins have been rarely documented.[5][10] Due to each bite taking a tiny amount of blood, chronic or severe infestation may lead to anemia.[5] Bacterial skin infection may occur due to skin break down from scratching.[5][11] Systemic poisoning may occur if the bites are numerous.[12] Exposure to bed bugs may trigger an asthma attack via the effects of airborne allergens although evidence of this association is limited.[5] There is no evidence that bed bugs transmit infectious diseases[5][7] even though they appear physically capable of carrying pathogens and this possibility has been investigated.[3][5] The bite itself may be painful thus resulting in poor sleep and worse work performance.[5]

Similar to humans, pets can also be bitten by bed bugs. The signs left by the bites are the same as in case of people and cause identical symptoms (skin irritation, scratching etc).[citation needed]

Insect

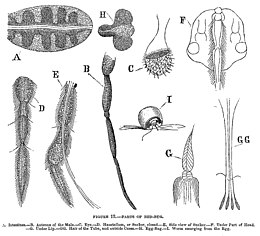

Bed bug infestations are primarily the result of two species of insects from genus Cimex: Cimex lectularius (the common bed bug) and Cimex hemipterus.[3] These insects feed exclusively on blood and may survive a year without eating.[3] Adult Cimex are light brown to reddish-brown, flat, oval, and have no hind wings. The front wings are vestigial and reduced to pad-like structures. Adults grow to 4–5 mm (0.16–0.20 in) long and 1.5–3 mm (0.059–0.118 in) wide. Bed bugs are unable to jump or fly.[13]

Bed bugs have five immature nymph life stages and a final sexually mature adult stage.[14] They shed their skins through ecdysis at each stage, discarding their outer exoskeleton.[15] Newly hatched nymphs are translucent, lighter in color, and become browner as they moult and reach maturity. Bed bugs may be mistaken for other insects, such as booklice, small cockroaches, or carpet beetles; however, when warm and active, their movements are more ant-like, and like most other true bugs, they emit a characteristic disagreeable odor when crushed.

Bed bugs are obligatory bloodsuckers. They have mouth parts that saw through the skin and inject saliva with anticoagulants and painkillers. Sensitivity of humans varies from extreme allergic reaction to no reaction at all (about 20%). The bite usually produces swelling with no red spot, but when many bugs feed on a small area, reddish spots may appear after the swelling subsides.[16] Bedbugs prefer exposed skin, preferably the face, neck, and arms of a sleeping person.

Bed bugs are attracted to their hosts primarily by carbon dioxide, secondarily by warmth, and also by certain chemicals.[4][17][18][19] Cimex lectularius feeds only every five to seven days, which suggests that it does not spend the majority of its life searching for a host. When a bed bug is starved, it leaves its shelter and searches for a host. It returns to its shelter after successful feeding or if it encounters exposure to light.[20] Cimex lectularius aggregate under all life stages and mating conditions. Bed bugs may choose to aggregate because of predation, resistance to desiccation, and more opportunities to find a mate. Airborne pheromones are responsible for aggregations.[21]

Spread

Infestation is rarely caused by a lack of hygiene.[8] Transfer to new places is usually in the personal items of the human they feed upon.[3] Dwellings can become infested with bed bugs in a variety of ways, such as:

- Bugs and eggs inadvertently brought in from other infested dwellings on a visiting person's clothing or luggage;

- Infested items (such as furniture especially beds or couches, clothing, or backpacks) brought in a home or business;

- Proximity of infested dwellings or items, if easy routes are available for travel, e.g. through ducts or false ceilings;

- Wild animals (such as bats or birds)[22][23] that may also harbour bed bugs or related species such as the bat bug;

- People visiting an infested area (e.g. dwelling, means of transport, entertainment venue, or lodging) and carrying the bugs to another area on their clothing, luggage, or bodies. Bedbugs are increasingly found in air travel.[24]

Though bed bugs will opportunistically feed on pets, they do not live or travel on the skin of their hosts, and pets are not believed to be a factor in their spread.[25]

Diagnosis

A definitive diagnosis of health effects due to bed bugs requires a search for and finding of the insect in the sleeping environment as symptoms are not sufficiently specific.[5] Bed bugs classically form a line of bites colloquially referred to as "breakfast, lunch, and dinner" and rarely feed in the armpit or behind the knee which may help differentiate it from other biting insects.[4] If the number in a house is large a pungent sweet odor may be described.[4] There are specially trained dogs that can detect this smell.[2]

Detection

Bed bugs can exist singly, but tend to congregate once established. Although strictly parasitic, they spend only a tiny fraction of their lifecycles physically attached to hosts. Once a bed bug finishes feeding, it relocates to a place close to a known host, commonly in or near beds or couches in clusters of adults, juveniles, and eggs—which entomologists call harborage areas or simply harborages to which the insect returns after future feedings by following chemical trails. These places can vary greatly in format, including luggage, inside of vehicles, within furniture, among bedside clutter—even inside electrical sockets and nearby laptop computers. Bed bugs may also nest near animals that have nested within a dwelling, such as bats, birds,[23] or rodents. They are also capable of surviving on domestic cats and dogs, though humans are the preferred host of C. lectularius.[26]

Bed bugs can also be detected by their characteristic smell of rotting raspberries.[27] Bed bug detection dogs are trained to pinpoint infestations, with a possible accuracy rate between 11% and 83%.[6] Homemade detectors have been developed.[28][29]

-

Eggs and two adults found inside a dresser

-

Fecal spot

-

Bed bug on carpet

-

Infested mattress

Differential diagnosis

Other possible conditions with which these conditions can be confused include scabies, gamasoidosis, allergic reactions, mosquito bites, spider bites, chicken pox and bacterial skin infections.[5]

Prevention

To prevent bringing home bed bugs, travelers are advised to take precautions after visiting an infested site: generally, these include checking shoes on leaving the site, changing clothes outside the house before entering, and putting the used clothes in a clothes dryer outside the house. When visiting a new lodging, it is advised to check the bed before taking suitcases into the sleeping area, and putting the suitcase on a raised stand to make bedbugs less likely to crawl in. An extreme measure would be putting the suitcase in the tub. Clothes should be hung up or left in the suitcase, and never left on the floor.[30] The founder of a company dedicated to bedbug extermination said that 5% of hotel rooms he books into were infested. He advised people never to sit down on public transport; check office chairs, plane seats, and hotel mattresses; and monitor and vacuum home beds once a month.[31]

Management

Treatment of bedbug bites requires keeping the person from being repeatedly bitten, and possible symptomatic use of antihistamines and corticosteroids (either topically or systemically).[5] There however is no evidence that medications improve outcomes, and symptoms usually resolve without treatment in 1–2 weeks.[3][4]

Avoiding repeated bites can be difficult, since it usually requires eradicating bed bugs from a home or workplace; eradication frequently requires a combination of non-pesticide approaches.[3] Once established, bed bugs are extremely difficult to get rid of.[3]

Mechanical approaches, such as vacuuming up the insects and heat-treating or wrapping mattresses, are effective.[3][6][13] An hour at a temperature of 45 °C (113 °F) or over, or two hours at less than −17 °C (1 °F) kills them.[6] This may include a domestic clothes drier for fabric or a commercial steamer. Bed bugs and their eggs will die on contact when exposed to surface temperatures above 180 °F (82 °C) and a steamer can reach well above 230 °F (110 °C).[16][32] A study found 100% mortality rates for bed bugs exposed to temperatures greater than 50 °C (122 °F) for more than 2 minutes. The study recommended maintaining temperatures of above 48 °C (118 °F) for more than 20 min to effectively kill all life stages of bed bugs, and because in practice treatment times of 6 to 8 hours are used to account for cracks and indoor clutter.[33] This method is expensive and has caused fires.[6][16] Starving bedbugs is not effective, as they can survive without eating for 100 to 300 days, depending on temperature.[6]

As of 2020 commercial insecticides are not recommended.[13] This is because no truly effective insecticides are available.[6] Resistance to pesticides has increased significantly over time, and there are concerns about harm to health from their use.[3] Insecticides that have historically been found effective include pyrethroids, dichlorvos, and malathion.[4] The carbamate insecticide propoxur is highly toxic to bed bugs, but it has potential toxicity to children exposed to it, and the US Environmental Protection Agency has been reluctant to approve it for indoor use.[34] Boric acid, occasionally applied as a safe indoor insecticide, is not effective against bed bugs[35] because they do not groom.[36]

Epidemiology

Bed bugs occur around the world.[37] Before the 1950s about 30% of houses in the United States had bedbugs.[2] Rates of infestation in developed countries, while decreasing from the 1930s to the 1980s, have increased dramatically since the 1980s.[3][4][37] This fall is believed to be partly due to the use of DDT to kill cockroaches.[38] The invention of the vacuum cleaner and simplification of furniture design may have also played a role in the decrease.[38] Others believe it might simply be the cyclical nature of the organism.[39]

The dramatic increase in bedbug populations in the developed world, which began in the 1980s, is thought to be due to greater foreign travel, increased immigration from the developing world to the developed world, more frequent exchange of second-hand furnishings among homes, a greater focus on control of other pests, resulting in neglect of bed bug countermeasures, and increasing bedbug resistance to pesticides.[4][40] Lower cockroach populations due to insecticide use may have aided bed bugs' resurgence, since cockroaches are known to sometimes predate them.[41] Bans on DDT and other potent pesticides may have also contributed.[42][43]

The U.S. National Pest Management Association reported a 71% increase in bed bug calls between 2000 and 2005.[44] The number of reported incidents in New York City alone rose from 500 in 2004 to 10,000 in 2009.[45] In 2013, Chicago was listed as the number 1 city in the United States for bedbug infestations.[46] As a result, the Chicago City Council passed a bed bug control ordinance to limit their spread. Additionally, bed bugs are reaching places in which they never established before, such as southern South America.[47][48]

The rise in infestations has been hard to track because bed bugs are not an easily identifiable problem and is one that people prefer not to discuss. Most of the reports are collected from pest-control companies, local authorities, and hotel chains.[49] Therefore, the problem may be more severe than is currently believed.[50]

Species

The common bed bug (C. lectularius) is the species best adapted to human environments. It is found in temperate climates throughout the world. Other species include Cimex hemipterus, found in tropical regions, which also infests poultry and bats, and Leptocimex boueti, found in the tropics of West Africa and South America, which infests bats and humans. Cimex pilosellus and Cimex pipistrella primarily infest bats, while Haematosiphon inodora, a species of North America, primarily infests poultry.[51]

History

Cimicidae, the ancestor of modern bed bugs, first emerged approximately 115 million years ago, more than 30 million years before bats—their previously presumed initial host—first appeared. From unknown ancestral hosts, a variety of different lineages evolved which specialized in either bats or birds. The common (C. lectularius) and tropical bed bug (C. hemipterus), split 40 million years before Homo evolution. Humans became hosts to bed bugs through host specialist extension (rather than switching) on three separate occasions.[52][53]

Bed bugs were mentioned in ancient Greece as early as 400 BC, and were later mentioned by Aristotle. Pliny's Natural History, first published circa AD 77 in Rome, claimed bed bugs had medicinal value in treating ailments such as snake bites and ear infections. Belief in the medicinal use of bed bugs persisted until at least the 18th century, when Guettard recommended their use in the treatment of hysteria.[54]

Bed bugs were first mentioned in Germany in the 11th century, in France in the 13th century, and in England in 1583,[55] though they remained rare in England until 1670. Some in the 18th century believed bed bugs had been brought to London with supplies of wood to rebuild the city after the Great Fire of London (1666). Giovanni Antonio Scopoli noted their presence in Carniola (roughly equivalent to present-day Slovenia) in the 18th century.[56][57]

Traditional methods of repelling and/or killing bed bugs include the use of plants, fungi, and insects (or their extracts), such as black pepper;[58] black cohosh (Actaea racemosa); Pseudarthria hookeri; Laggera alata (Chinese yángmáo cǎo | 羊毛草);[16] Eucalyptus saligna oil;[59][60] henna (Lawsonia inermis or camphire);[61] "infused oil of Melolontha vulgaris" (presumably cockchafer); fly agaric (Amanita muscaria); tobacco; "heated oil of Terebinthina" (i.e. true turpentine); wild mint (Mentha arvensis); narrow-leaved pepperwort (Lepidium ruderale); Myrica spp. (e.g. bayberry); Robert geranium (Geranium robertianum); bugbane (Cimicifuga spp.); "herb and seeds of Cannabis"; "opulus" berries (possibly maple or European cranberrybush); masked hunter bugs (Reduvius personatus), "and many others".[62]

In the mid-19th century, smoke from peat fires was recommended as an indoor domestic fumigant against bed bugs.[63]

Dusts have been used to ward off insects from grain storage for centuries, including plant ash, lime, dolomite, certain types of soil, and diatomaceous earth or Kieselguhr.[64] Of these, diatomaceous earth in particular has seen a revival as a nontoxic (when in amorphous form) residual pesticide for bed bug abatement. While diatomaceous earth often performs poorly, silica gel may be effective.[65][66]

Basket-work panels were put around beds and shaken out in the morning in the UK and in France in the 19th century. Scattering leaves of plants with microscopic hooked hairs around a bed at night, then sweeping them up in the morning and burning them, was a technique reportedly used in Southern Rhodesia and in the Balkans.[67]

Bean leaves have been used historically to trap bedbugs in houses in Eastern Europe. The trichomes on the bean leaves capture the insects by impaling the feet (tarsi) of the insects. The leaves are then destroyed.[68]

20th century

Before the mid-20th century, bed bugs were very common. According to a report by the UK Ministry of Health, in 1933, all the houses in many areas had some degree of bed bug infestation.[49] The increase in bed bug populations in the early 20th century has been attributed to the advent of electric heating, which allowed bed bugs to thrive year-round instead of only in warm weather.[69]

Bed bugs were a serious problem at US military bases during World War II.[70] Initially, the problem was solved by fumigation, using Zyklon Discoids that released hydrogen cyanide gas, a rather dangerous procedure.[70] Later, DDT was used to good effect.[70]

The decline of bed bug populations in the 20th century is often credited to potent pesticides that had not previously been widely available.[71] Other contributing factors that are less frequently mentioned in news reports are increased public awareness and slum clearance programs that combined pesticide use with steam disinfection, relocation of slum dwellers to new housing, and in some cases also follow-up inspections[how?] for several months after relocated tenants moved into their new housing.[69]

Society and culture

Legal action

Bed bugs are an increasing cause for litigation.[72] Courts have, in some cases, exacted large punitive damage judgments on some hotels.[73][74][75] Many of New York City's Upper East Side homeowners have been afflicted, but they tend to remain publicly silent in order not to ruin their property values and be seen as suffering a blight typically associated with the lower classes.[76] Local Law 69 in New York City requires owners of buildings with three or more units to provide their tenants and potential tenants with reports of bedbug history in each unit. They must also prominently post these listings and reports in their building.[77]

Literature

- "Good night, sleep tight, don't let the bed bugs bite," is a traditional saying.[78]

- The Bedbug (Russian: Клоп, Klop) is a play by Vladimir Mayakovsky written in 1928–1929

- How the Bed Bug Infiltrated Our Bedrooms and Took Over the World is a book, written by Brooke Borel

Research

Bed bug secretions can inhibit the growth of some bacteria and fungi; antibacterial components from the bed bug could be used against human pathogens, and be a source of pharmacologically active molecules as a resource for the discovery of new drugs.[79]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 446. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 Ibrahim, O; Syed, UM; Tomecki, KJ (March 2017). "Bedbugs: Helping your patient through an infestation". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 84 (3): 207–211. doi:10.3949/ccjm.84a.15024. PMID 28322676.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 Jerome Goddard; Richard deShazo (2009). "Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) and clinical consequences of their bites". Journal of the American Medical Association. 301 (13): 1358–1366. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.405. PMID 19336711.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Kolb A, Needham GR, Neyman KM, High WA (2009). "Bedbugs". Dermatol Ther. 22 (4): 347–52. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01246.x. PMID 19580578.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 Doggett SL, Russell R (November 2009). "Bed bugs – What the GP needs to know". Aust Fam Physician. 38 (11): 880–4. PMID 19893834.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Doggett, SL; Dwyer, DE; Peñas, PF; Russell, RC (January 2012). "Bed bugs: clinical relevance and control options". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 25 (1): 164–92. doi:10.1128/CMR.05015-11. PMC 3255965. PMID 22232375.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "Bed Bugs FAQs". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2 May 2017. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Hildreth CJ, Burke AE, Glass RM (April 2009). "JAMA patient page. Bed bugs". JAMA. 301 (13): 1398. doi:10.1001/jama.301.13.1398. PMID 19336718.

- ↑ Susan C. Jones (January 2004). "Extension Fact Sheet "Bed Bugs, Injury"" (PDF). Ohio State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Bircher, Andreas J (2005). "Systemic Immediate Allergic Reactions to Arthropod Stings and Bites". Dermatology. 210 (2): 119–127. doi:10.1159/000082567. PMID 15724094.

- ↑ "How to Manage Pests Pests of Homes, Structures, People, and Pets". UC IPM Online (Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program, UC Davis). Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Americana, 1996 ed., v. 3, p. 431

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Parola, Philippe; Izri, Arezki (4 June 2020). "Bedbugs". New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (23): 2230–2237. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1905840.

- ↑ Xavier Bonnefoy; Helge Kampen; Kevin Sweeney. "Public Health Significance of Urban Pests" (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 136. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Shukla; Upadhyaya (2009). Economic Zoology (Fourth ed.). Rastogi. p. 73. ISBN 978-81-7133-876-4. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Quarles, William (March 2007). "Bed Bugs Bounce Back" (PDF). IPM Practitioner. 24 (3/4): 1–8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ↑ Anderson, J. F.; Ferrandino, F. J.; McKnight, S.; Nolen, J.; Miller, J. (2009). "A carbon dioxide, heat and chemical lure trap for the bed bug, Cimex lectularius" (PDF). Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 23 (2): 99–105. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00790.x. PMID 19499616. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ↑ Singh, Narinderpal; Wang, Changlu; Cooper, Richard; Liu, Chaofeng (2012). "Interactions among Carbon Dioxide, Heat, and Chemical Lures in Attracting the Bed Bug, Cimex lectularius L. (Hemiptera: Cimicidae)". Psyche. 2012: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2012/273613.

- ↑ Wang, Changlu; Gibb, Timothy; Bennett, Gary W.; McKnight, Susan (August 2009). "Bed bug (Heteroptera: Cimicidae) attraction to pitfall traps baited with carbon dioxide, heat, and chemical lure" (PDF). Journal of Economic Entomology. 102 (4): 1580–5. doi:10.1603/029.102.0423. PMID 19736771. 102(4):1580-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Reis Matthew D., Miller Dini M. (2011). "Host Searching and Aggregation Activity of Recently Fed and Unfed Bed Bugs (Cimex Lectularius L.)". Insects. 2 (4): 186–94. doi:10.3390/insects2020186. PMC 4553457. PMID 26467621.

- ↑ Margie Pfiester; Philip G. Koehler; Roberto M. Pereira (2009). "Effect of Population Structure and Size on Aggregation Behavior Of(Hemiptera: Cimicidae)". Journal of Medical Entomology. 46 (5): 1015–020. doi:10.1603/033.046.0506. PMID 19769030.

- ↑ Potter, Michael F. "BED BUGS". University of Kentucky College of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Steelman, C.D. 2000. Biology and control of bed bugsArchive, Cimex lectularius, in poultry houses. Avian Advice 2: 10,15.

- ↑ Haiken, Melanie. "Bed Bugs on Airplanes?! Yikes! How to Fly Bed Bug-Free". Forbes. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ↑ "The Truth About Bedbugs: Debunking the Myths". PAWS SF. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ↑ Susan L. Woodward; Joyce A. Quinn (30 September 2011). Encyclopedia of Invasive Species: From Africanized Honey Bees to Zebra Mussels: From Africanized Honey Bees to Zebra Mussels. ABC-CLIO. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-313-38221-5. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ Anderson, AL; Leffler, K (May 2008). "Bedbug infestations in the news: a picture of an emerging public health problem in the United States" (PDF). Journal of Environmental Health. 70 (9): 24–7, 52–3. PMID 18517150. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012.

- ↑ "7 On Your Side: Get rid of bed bugs for less than $15". Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ "Detecting Bed Bugs Using Bed Bug Monitors (from Rutgers NJAES)". Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Kate Wong (23 January 2012). "Bed Bug Confidential: An Expert Explains How to Defend against the Dreaded Pests". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ↑ Sherwood, Harriet (19 August 2018). "Bedbugs plague hits British cities". The Observer. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ↑ "Using Steamers to Control Bed Bugs". 22 June 2016. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Hulasare, Raj. "Fundamental Research on the Efficacy of Heat on Bed Bugs and Heat Transfer in Mattresses".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ [ York Times. In Search of a Bedbug Solution.] Published: 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "Opinion | In Search of a Bedbug Solution". The New York Times. 4 September 2010. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ↑ Miller, Dini (11 August 2008). "Bed bugs (hemiptera: cimicidae: Cimex spp.)". In John L. Capinera (ed.). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 414. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Heukelbach, J; Hengge, UR (2009). "Bed bugs, leeches and hookworm larvae in the skin". Clinics in Dermatology. 27 (3): 285–90. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2008.10.008. PMID 19362691.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Krause-Parello CA, Sciscione P (April 2009). "Bedbugs: an equal opportunist and cosmopolitan creature". J Sch Nurs. 25 (2): 126–32. doi:10.1177/1059840509331438. PMID 19233933.

- ↑ Xavier Bonnefoy; Helge Kampen; Kevin Sweeney. "Public Health Significance of Urban Pests" (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 131. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Romero A, Potter MF, Potter DA, Haynes KF (2007). "Insecticide Resistance in the Bed Bug: A Factor in the Pest's Sudden Resurgence?". Journal of Medical Entomology. 44 (2): 175–178. doi:10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[175:IRITBB]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-2585. PMID 17427684.

- ↑ Gulati, A. N. (1930). "Do Cockroaches eat Bed Bugs?". Nature. 125 (3162): 858. Bibcode:1930Natur.125..858G. doi:10.1038/125858a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ↑ Bankhead, Charles (27 August 2015). "Bed Bug Resurgence a Multifactorial Issue: Hygiene, insecticide bans, globalization all contribute". Meeting Coverage. MedPage Today. Archived from the original on 28 August 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ Davies, T. G. E.; Field, L. M.; Williamson, M. S. (2012). "The re-emergence of the bed bug as a nuisance pest: implications of resistance to the pyrethroid insecticides". Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 26 (3): 241–254. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2915.2011.01006.x. ISSN 1365-2915. PMID 22235873.

- ↑ Voiland, Adam (16 July 2007). "You May not be Alone". U.S. News & World Report. 143 (2): 53–54. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011.

- ↑ Megan Gibson (19 August 2010). "Are Bedbugs Taking Over New York City?". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Metropolitan Tenants Organization (16 July 2013). "Chicago Council passes Bed Bug Ordinance". Metropolitan Tenants Organization website. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Faúndez E. I., Carvajal M. A. (2014). "Bed bugs are back and also arriving is the southernmost record of Cimex lectularius (Heteroptera: Cimicidae) in South America". Journal of Medical Entomology. 51 (5): 1073–1076. doi:10.1603/me13206. PMID 25276939.

- ↑ Faúndez E. I. (2015). "Primeros registros de la chinche de cama Cimex lectularius Linneo, 1755 (Hemiptera: Cimicidae) en la Isla Tierra del Fuego (Chile)". Arquivos Entomolóxicos. 14: 279–280.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Boase, Clive J. (April 2004). "Bed-bugs – reclaiming our cities". Biologist. 51: 1–4. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ↑ Scarupa, M.D.; Economides, A. (2006). "Bedbug bites masquerading as urticaria". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 117 (6): 1508–1509. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.03.034. PMID 16751024.

- ↑ Cranshaw, W.S.; Camper, M.; Peairs, F.B. (Feb 2009). "Bat Bugs and Bed Bugs". Colorado State University Extension. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ↑ Reinhardt, Klaus; Willassen, Endre; Morrow, Edward H.; Simov, Nikolay; Naylor, Richard; Lehnert, Margie P.; McFadzen, Mary; Khan, Faisal Ali Anwarali; Faundez, Eduardo I. (3 June 2019). "Bedbugs Evolved before Their Bat Hosts and Did Not Co-speciate with Ancient Humans". Current Biology. 29 (11): 1847–1853.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.048. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 31104934. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Reinhardt, Klaus; Willassen, Endre; Morrow, Edward H.; Simov, Nikolay; Naylor, Richard; Khan, Faisal Ali Anwarali; Lehnert, Margie P.; McFadzen, Mary; Faundez, Eduardo I. (11 July 2018). "A molecular phylogeny of bedbugs elucidates the evolution of host associations and sex-reversal of reproductive trait diversification". bioRxiv: 367425. doi:10.1101/367425. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Smith, William (1847). A dictionary of Greek and Roman antiquities – Sir William Smith – Google Boeken. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ Mullen, Gary R.; Durden, Lance A. (8 May 2009). Medical and Veterinary Entomology (Second ed.). Academic Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-12-372500-4.

- ↑ John Southall. "That soon after the Fire of London, in some of the new-built Houses they were observ'd to appear, and were never noted to have been seen in the old, tho' they were then so few, as to be little taken notice of; yet as they were only seen in Firr-Timber, 'twas conjectured they were then first brought to England in them; of which most of the new Houses were partly built, instead of the good Oak destroy'd in the old". A Treatise of Buggs [sic], pp. 16–17. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Wolff; Johann Philip Wolff. "According to Scopoli's 2nd work (loc. cit.), found in Carniola and adjoining regions. According to Linnaeus' second work on exotic insects (loc. cit.), before the era of health, already in Europe, seldom observed in England before 1670". Icones Cimicum descriptionibus illustratae. p. 127. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

fourth fascicle (1804)

- ↑ George Orwell, Down and Out in Paris and London, 1933

- ↑ Schaefer, C.W.; Pazzini, A.R. (28 July 2000). Heteroptera of Economic Importance. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 525. ISBN 978-0-8493-0695-2. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Kambu, Kabangu; Di Phanzu, N.; Coune, Claude; Wauters, Jean-Noël; Angenot, Luc (1982). "Contribution à l'étude des propriétés insecticides et chimiques d'Eucalyptus saligna du Zaïre (Contribution to the study of insecticide and chemical properties of Eucalyptus saligna from Zaire ( Congo))". Plantes Médicinales et Phytothérapie. 16 (1): 34–38. hdl:2268/14438.

- ↑ "Getting Rid of Bed-Bugs". Grubstreet.rictornorton.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ "Icones Cimicum descriptionibus illustratae". Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ "Peat and peat mosses". Scientific American. 3 (39): 307. 17 June 1848. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican06171848-307b. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Hill, Stuart B. (May 1986). "Diatomaceous Earth: A Non Toxic Pesticide". Macdonald J. 47 (2): 14–42. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ Michael F. Potter; Kenneth F. Haynes; Chris Christensen; T. J. Neary; Chris Turner; Lawrence Washburn; Melody Washburn (December 2013). "Diatomaceous Earth: Where Do Bed Bugs Stand When the Dust Settles?". PCT Magazine (12): 72. ISSN 0730-7608. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Michael F. Potter; Kenneth F. Haynes; Jennifer R. Gordon; Larry Washburn; Melody Washburn; Travis Hardin (August 2014). "Silica Gel: A Better Bed Bug Desiccant". PCT Magazine (8): 76. ISSN 0730-7608. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Boase, C. (2001). "Bedbugs – back from the brink". Pesticide Outlook. 12 (4): 159–162. doi:10.1039/b106301b.

- ↑ Szyndler, M.W.; Haynes, K.F.; Potter, M.F.; Corn, R.M.; Loudon, C. (2013). "Entrapment of bed bugs by leaf trichomes inspires microfabrication of biomimetic surfaces". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 10 (83): 20130174. doi:10.1098/rsif.2013.0174. ISSN 1742-5662. PMC 3645427. PMID 23576783.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Potter, Michael F. (2011). "The History of Bed Bug Management – With Lessons from the Past" (PDF). American Entomologist. 57: 14–25. doi:10.1093/ae/57.1.14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Gerberg, Eugene J. (16 November 2008). "Entomologists in World War II" (PDF). Proceedings of the DOD Symposium, 'Evolution of Military Medical Entomology', Held 16 November 2008, Reno, NV. Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ Newsweek (8 September 2010). "The Politics of Bedbugs". Archived from the original on 21 October 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ Initi, John "Sleeping with the Enemy" Maclean's, 14 January 2008, Vol. 121, Issue 1, p54–56

- ↑ Kimberly Stevens (25 December 2003). "Sleeping with the Enemy". New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ↑ Archive BURL MATHIAS and DESIREE MATHIAS, Plaintiffs-Appellees/Cross-Appellants

- ↑ Shavell, Steven (2007), "On the Proper Magnitude of Punitive Damages: Mathias v. Accor Economy Lodging, Inc." (PDF), Harvard Law Review, 120: 1223–1227, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2008, retrieved 16 January 2010

- ↑ Marshall Sella (2 May 2010). "Bedbugs in the Duvet: An infestation on the Upper East Side". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ↑ Bailey, Adam Leitman (16 January 2018). "The Newest New York City Real Estate Laws That Property Owners and Occupants Must Know in 2018". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ↑ Berg, Rebecca (2010). "Bed Bugs: The Pesticide Dilemma". Journal of Environmental Health. 72 (10): 32–35. PMID 20556941.

- ↑ Stephen L Doggett; Dominic E. Dwyer; Richard C Russell (January 2012). "Bed Bugs Clinical Relevance and Control Options". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 25 (1): 164–92. doi:10.1128/CMR.05015-11. PMC 3255965. PMID 22232375.

External links

- Bed bug Archived 11 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine on the University of Florida/IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

- National Geographic segment on Bed bugs on YouTube

- Bed bugs Archived 4 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine – University of Sydney and Westmead Hospital Department of Medical Entomology

- Understanding and Controlling Bed Bugs – National Pesticide Information Center Archived 22 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- CISR: Center for Invasive Species Research Archived 13 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine More information on Bed Bugs, with lots of photos and video

- EPA bedbugs information page Archived 28 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- A Code of Practice for the Control of Bed Bugs in Australia, ICPMR & AEPMA, Sydney Australia, September 2011. ISBN 1-74080-135-0."Bed Bug Home Page". Bedbug.org.au. 14 October 2005. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2018

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Wikipedia articles needing clarification from June 2019

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Bed bug

- Cimicidae

- Haematophagy

- Household pest insects

- Parasitic bugs

- RTT