Loss of smell

| Loss of smell | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Anosmia, smell blindness,[1] odor blindness | |

| |

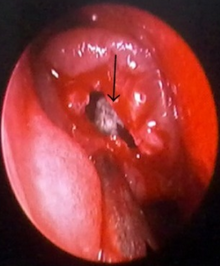

| Inflamed nasal mucosa causing anosmia | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology |

| Symptoms | Loss of the ability to detect one or more odors[1][2] |

| Types | Partial, total[2] |

| Causes | Blockage of the noses, dysfunction of the neurons involved with smell[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Hyposmia, parosmia, phantosmia[3] |

| Treatment | Depends on the underlying cause[3] |

| Frequency | 3 to 20% of those over 40 years[3][4] |

Loss of smell, technically known as anosmia, is the loss of the ability to detect one or more odors.[1][2] It may be temporary or permanent.[3] Some cases are present at birth while others are acquired later in life.[3] The inability to identify harmful smell can be dangerous and enjoyment of food can be affected.[3]

About 50 to 70% of cases are due to blockage of the nose, such as from inflammation or nasal polyps.[3] Other cases are due to dysfunction of the neurons involved with smell as a result of head injury, tumors, aging, toxins, or certain genetic condition.[3] It may also be a symptom of COVID-19, particularly early in infection.[5] Determining the underlying cause involves taking into account other symptoms and examination.[3] Some centers have the ability to do more detailed analysis.[3] It differs from hyposmia, which is a decreased sensitivity to some or all smells.[2]

Treatment depends on the underlying cause.[3] Steroid nose sprays may help with a number of causes of blockage of the nose.[3] Surgery may be an option for some sinus problems.[3] There is no specific treatment for cases due to dysfunction of neurons, though some cases may improve over days to years.[3]

About 3 to 20% of people age over 40 are affected.[3][4] The condition becomes more common with age, affecting about 40% of those over the age of 80.[3] One of the earliest documented cases of loss of smell following head trauma, was a case reported by Hughling Jackson in 1864 in London.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Anosmia is the inability to smell.[1] It may be partial or total, and can be specific to certain smells.[2] Smell can be lost from one or both nostrils, and it may not always appear obvious.[7] Reduced sensitivity to some or all smells is hyposmia.[2]

Anosmia can have a number of harmful effects.[8] People with sudden onset anosmia may find food less appetizing and may be unaware of their own body odour.[9] Loss of smell can also be dangerous because it hinders the detection of gas leaks, fire, and spoiled food.[9] The common view of loss of smell as trivial can make it more difficult for a person to receive the same types of medical aid as someone who has lost other senses, such as hearing or sight.[9]

Losing an established and sentimental smell memory (e.g. the smell of grass, of the grandparents' attic, of a particular book, of loved ones, or of oneself) has been known to cause feelings of depression.[10]

Loss of the ability to smell may lead to the loss of libido, though this usually does not apply to loss of smell present at birth.[10]

Often people who have loss of smell at birth report that they pretended to be able to smell as children because they thought that smelling was something that older/mature people could do, or did not understand the concept of smelling but did not want to appear different from others. When children get older, they often realize and report to their parents that they do not actually possess a sense of smell, often to the surprise of their parents.[citation needed]

A study done on patients suffering from anosmia found that when testing both nostrils, there was no anosmia revealed; however, when testing each nostril individually, tests showed that the sense of smell was usually affected in only one of the nostrils as opposed to both. This demonstrated that unilateral anosmia is not uncommon in anosmia patients.[11]

Causes

Reduced ability to smell may occur as part of normal ageing.[12] However, loss of smell is common in conditions that cause a runny nose or inflammation in the nose.[12] The most common neurological cause is damage to the olfactory nerve from trauma to the head.[12] If the loss of smell is from one nostril only, a tumour may be suspected.[12] Some medications, recreational drugs, alcohol[13] and smoking can also affect the ability to smell.[12]

Some people may be born with the inability to smell, such as in Kallmann syndrome.[12] The occurrence within some families suggests that some congenital anosmia may follow an autosomal dominant pattern.[14] Anosmia may very occasionally be an early sign of a degenerative brain disease such as Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease.[12] The association with depression is not clear.[15][16]

In 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, new onset loss of smell became a well-established symptom of COVID-19, particularly in the early stages of mild to moderate infection, where its prevalence reaches around 85%, and where it is frequently the first sign or only sign of the disease.[5][17] Loss of smell has also been found to be more predictive of COVID-19 than all other symptoms, including fever, cough or fatigue, based on a survey of 2 million participants in the UK and US.[18]

Prolonged use of some nasal sprays can cause loss of smell,[9] particularly those that cause vasoconstriction in the nose.[19] Anosmia can also be caused by nasal polyps.[15]

It can be caused by chronic meningitis and neurosyphilis that would increase intracranial pressure over a long period of time.[20] Loss of smell has been reported in a case in which a 66-year-old male was treated with amiodarone for ventricular tachycardia.[21] Olfactory neuroblastoma, an exceedingly rare cancer that originates in or near the olfactory nerve can present with loss of smell and may accompany chronic sinusitis for several years before diagnosis.[22]

Causes and contributory factors for dysfunction or loss of smell include:

Congenital

- Kallmann syndrome[12][13]

- Isolated congenital anosmia[23]

Nerve and brain

Drugs and toxins

- Antibiotics[13]

- Acrylates, methacrylates[27]

- Cadmium[13][28][29]

- Zicam[15]

- Propylthiouracil[13]

- Amphetamines[13]

- Levodopa[13]

- Alcohol effects[13]

- Smoking[30]

- Intranasal drug use

- Snakebite[31]

- Exposure to a chemical that burns the inside of the nose[13]

- Zinc-based intranasal cold products, including remedies labelled as "homeopathic"[32]

Sinus and respiratory

Infection

Trauma

- Head injury[39]

Surgical complications

Deficiencies

Other

- Fibromyalgia

- Hypoglycaemia

- Pregnancy[13]

- Hypothyroidism

- Diabetes

- Liver or kidney disease

- Cushing's syndrome

- Stroke

- Epilepsy

- Radiation therapy[13]

- Old age[40]

- Samter's triad also known as AERD (aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease)

- Foster Kennedy syndrome[7]

- Neurotropic virus[41]

- Schizophrenia[13][42]

- Bell's Palsy or nerve paralysis and damage

- Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

- Refsum's disease[13]

- Adrenergic agonists or withdrawal from alpha blockers (vasoconstriction)

- Sarcoidosis[43]

- Paget's disease of bone[44]

- Cerebral aneurysm[45]

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis

- Idiopathic anosmia (cause cannot be determined)[3]

Diagnosis

Both nostrils are tested separately to determine whether one or both nostrils are affected.[11]

Anosmia can be diagnosed by doctors by using acetylcysteine tests. Doctors will begin with a detailed elicitation of history. Then the doctor will ask for any related injuries in relation to anosmia which could include upper respiratory infections or head injury. Psychophysical Assessment of order and taste identification can be used to identify anosmia. A nervous system examination is performed to see if the cranial nerves are damaged.[46] The diagnosis, as well as the degree of impairment, can now be tested much more efficiently and effectively than ever before thanks to "smell testing kits" that have been made available as well as screening tests which use materials that most clinics would readily have.[47] Occasionally, after accidents, there is a change in a patient's sense of smell. Particular smells that were present before are no longer present. On occasion, after head traumas, there are patients who have unilateral anosmia. The sense of smell should be tested individually in each nostril.[11]

Many cases of congenital anosmia remain unreported and undiagnosed. Since the disorder is present from birth the individual may have little or no understanding of the sense of smell, hence is unaware of the deficit.[48] It may also lead to reduction of appetite.[49]

Treatment

Though anosmia caused by brain damage cannot be treated, anosmia caused by inflammatory changes in the mucosa may be treated with glucocorticoids. Reduction of inflammation through the use of oral glucocorticoids such as prednisone, followed by long term topical glucocorticoid nasal spray, would easily and safely treat the anosmia. A prednisone regimen is adjusted based on the degree of the thickness of mucosa, the discharge of oedema and the presence or absence of nasal polyps.[50] However, the treatment is not permanent and may have to be repeated after a short while.[50] Together with medication, pressure of the upper area of the nose must be mitigated through aeration and drainage.[51]

Anosmia caused by a nasal polyp may be treated by steroidal treatment or removal of the polyp.[52]

Although very early in development, gene therapy has restored a sense of smell in mice with congenital anosmia when caused by ciliopathy. In this case, a genetic condition had affected cilia in their bodies which normally enabled them to detect air-borne chemicals, and an adenovirus was used to implant a working version of the IFT88 gene into defective cells in the nose, which restored the cilia and allowed a sense of smell.[53][54]

Epidemiology

In the United States 3-20% of people age over 40 are affected by disturbance in smell.[3][4]

In 2012 smell was assessed in persons aged 40 years and older with rates of anosmia/severe hyposmia was 0.3% at age 40–49 rising to 14.1% at age 80+. Rates of hyposmia was much higher: 3.7% at age 40–49 and 25.9% at 80+.[55]

History

An early observation of loss of smell following trauma was documented in 1864 by Hughling Jackson in volume 1 of the London hospital reports, in which he recorded that a 50-year-old man who had fallen off his horse and suffered concussion and subsequently complained of an inability to smell.[6][56] Others shortly reported similar findings including reports with simultaneous loss of taste.[6]

Society and culture

Google searches for "smell", "loss of smell", "anosmia", and other similar terms increased since the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and strongly correlated with increases in daily cases and deaths.[57] Research into the mechanisms underlying these symptoms are currently ongoing.[58] While many countries list anosmia as an official COVID-19 symptom, some have developed "smell tests" as potential screening tools.[59][60] In 2020, the Global Consortium for Chemosensory Research, a collaborative research organization of international smell and taste researchers, formed to investigate loss of smell and related chemosensory symptoms.[61]

Terminology

The term derives from the New Latin anosmia, based on Ancient Greek ἀν- (an-) + ὀσμή (osmḗ, "smell"; another related term, hyperosmia, refers to an increased ability to smell). Some people may be anosmic for one particular odor, a condition known as "specific anosmia". The absence of the sense of smell from birth is known as congenital anosmia.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Coon D, Mitterer J (2014). "4. Sensation and perception". Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and Behavior. Boston: Cengage Learning. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-305-09187-0. LCCN 2014942026. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Jones, Nicholas (2010). "2. Making sense of symptoms". In Jones, Nicholas (ed.). Practical Rhinology. CRC Press. p. 24-25. ISBN 978-1-4441-0861-3. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 Li, Xi; Lui, Forshing (6 July 2020), "Anosmia", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29489163, archived from the original on 29 September 2020, retrieved 1 December 2020

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Boesveldt, Sanne; Postma, Elbrich M; Boak, Duncan; Welge-Luessen, Antje; Schöpf, Veronika; Mainland, Joel D; Martens, Jeffrey; Ngai, John; Duffy, Valerie B (September 2017). "Anosmia—A Clinical Review". Chemical Senses. 42 (7): 513–523. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjx025. ISSN 0379-864X. PMID 28531300. Archived from the original on 2020-12-24. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Srivastava, Piyush; Gupta, Nidhi (2020). "3. Clinical manifestations of coronavirus disease". In Prabhakar, Hemanshu; Kapoor, Indu; Mahajan, Charu (eds.). Clinical Synopsis of COVID-19: Evolving and Challenging. Springer. p. 31-40. ISBN 9789811586804. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Costanzo, Richard M.; Ward, John D.; Young, Harold F. (2012). "20. Olfaction and Head Injury". In Michael J. Serby (ed.). Science of Olfaction. Karen L. Chobor. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 546–548. ISBN 978-1-4612-2836-3. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Brazis, Paul W.; Masdeu, Joseph C.; Biller, José (2007). Localization in Clinical Neurology (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 125–130. ISBN 978-0-7817-9952-2. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- ↑ Toller, Steve Van (1 December 1999). "Assessing the Impact of Anosmia: Review of a Questionnaire's Findings". Chemical Senses. 24 (6): 705–712. doi:10.1093/chemse/24.6.705. ISSN 0379-864X. PMID 10587505. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Koçak, Tuğba; Altundağ, Aytuğ; Hummel, Thomas (2019). "13. Clinical assessment of olfactory disorders". In Cingi, Cemal; Muluk, Nuray Bayar (eds.). All Around the Nose: Basic Science, Diseases and Surgical Management. Switzerland: Springer. p. 111. ISBN 978-3-030-21216-2. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Heald C (December 27, 2006). "Sense and scent ability". BBC News. Archived from the original on March 28, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Harvey P (February 2006). "Anosmia". Practical Neurology. 6 (1): 65. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 Larner, A.J. (2010). A Dictionary of Neurological Signs (3rd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4419-7094-7. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 13.19 13.20 13.21 13.22 13.23 13.24 Campbell, William Wesley; DeJong, Russell N. (2005). "12. The olfactory nerve". DeJong's the Neurologic Examination. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 114–115. ISBN 0-7817-2767-7. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ↑ Waguespack, R. W. (1992). "Congenital Anosmia". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 118 (1): 10. doi:10.1001/archotol.1992.01880010012002. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Hawkes, Christopher H.; Doty, Richard L. (2017). "5. Non-neurodegenerative disorders of olfaction". Smell and Taste Disorders. Cambridge University Press. p. 182-247. ISBN 978-0-521-13062-2. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ↑ Kohli, Preeti; Soler, Zachary M.; Nguyen, Shaun A.; Muus, John S.; Schlosser, Rodney J. (July 2016). "The Association Between Olfaction and Depression: A Systematic Review". Chemical Senses. 41 (6): 479–486. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjw061. ISSN 0379-864X. PMC 4918728. PMID 27170667. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ Xydakis MS, Dehgani-Mobaraki P, Holbrook EH, Geisthoff UW, Bauer C, Hautefort C, et al. (September 2020). "Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 20 (9): 1015–1016. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30293-0. PMC 7159875. PMID 32304629.

- ↑ Menni C, Valdes AM, Freidin MB, Sudre CH, Nguyen LH, Drew DA, et al. (July 2020). "Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19". Nature Medicine. 26 (7): 1037–1040. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0916-2. PMC 7751267. PMID 32393804.

- ↑ Feldman, Heidi M.; Salinas, Maria A.; Tang, Brian G. (2012). "44. Sensory disorders". In Harfi, Harb A.; Stapleton, F. Bruder; Nazer, Hisham M.; OH, William; Whitley, Richard J. (eds.). Textbook of Clinical Pediatrics. London: Springer. p. 608. ISBN 978-3-642-02201-2. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ↑ "Anosmia". The Lancet. 241 (6228): 55. 1943. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)89085-6.

- ↑ Aronson, Jeffrey K. (2010). Side Effects of Drugs Annual: A Worldwide Yearly Survey of New Data and Trends in Adverse Drug Reactions. Elsevier. pp. 342–343. ISBN 978-0-444-53550-4. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Murphy, Barbara A.; Maulino, Joseph M.; Chung, Christine H.; Ely, Kim; Sinard, Robert; Cmelak, Anthony (2006). Raghavan, Derek; Meropol, Neal J.; Moots, Paul L.; Rose, Peter G.; Mayer, Ingrid A. (eds.). Textbook of Uncommon Cancer. John Wiley & Sons. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-470-03055-4. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|name-list-format=(help) - ↑ "Congenital anosmia | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ↑ Murphy C (April 1999). "Loss of olfactory function in dementing disease". Physiology & Behavior. 66 (2): 177–82. doi:10.1016/S0031-9384(98)00262-5. PMID 10336141. S2CID 26110446.

- ↑ Doty RL, Deems DA, Stellar S (August 1988). "Olfactory dysfunction in parkinsonism: a general deficit unrelated to neurologic signs, disease stage, or disease duration". Neurology. 38 (8): 1237–44. doi:10.1212/WNL.38.8.1237. PMID 3399075. S2CID 3009692.

- ↑ Leon-Sarmiento FE, Bayona EA, Bayona-Prieto J, Osman A, Doty RL (2012). "Profound olfactory dysfunction in myasthenia gravis". PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e45544. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745544L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045544. PMC 3474814. PMID 23082113.

- ↑ Schwartz BS, Doty RL, Monroe C, Frye R, Barker S (May 1989). "Olfactory function in chemical workers exposed to acrylate and methacrylate vapors". American Journal of Public Health. 79 (5): 613–8. doi:10.2105/AJPH.79.5.613. PMC 1349504. PMID 2784947.

- ↑ Rose CS, Heywood PG, Costanzo RM (June 1992). "Olfactory impairment after chronic occupational cadmium exposure". Journal of Occupational Medicine. 34 (6): 600–5. PMID 1619490.

- ↑ Rydzewski B, Sułkowski W, Miarzyńska M (1998). "Olfactory disorders induced by cadmium exposure: a clinical study". International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 11 (3): 235–45. PMID 9844306.

- ↑ Beverly J. Tepper; Iole Tomassini Barbarossa (2020). Taste, Nutrition and Health. MDPI. p. 276. ISBN 978-3-03928-444-3. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ↑ Churchman A, O'Leary MA, Buckley NA, Page CB, Tankel A, Gavaghan C, et al. (December 2010). "Clinical effects of red-bellied black snake (Pseudechis porphyriacus) envenoming and correlation with venom concentrations: Australian Snakebite Project (ASP-11)". The Medical Journal of Australia. 193 (11–12): 696–700. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb04108.x. PMID 21143062. S2CID 15915175. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ↑ Harris G (June 16, 2009). "F.D.A. Warns Against Use of Popular Cold Remedy". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ↑ Ta NH (January 2019). "Will we ever cure nasal polyps?". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 101 (1): 35–39. doi:10.1308/rcsann.2018.0149. PMC 6303820. PMID 30286644.

- ↑ Doty RL, Mishra A (March 2001). "Olfaction and its alteration by nasal obstruction, rhinitis, and rhinosinusitis". The Laryngoscope. 111 (3): 409–23. doi:10.1097/00005537-200103000-00008. PMC 7165948. PMID 11224769.

- ↑ Uytingco, Cedric R.; Green, Warren W.; Martens, Jeffrey R. (2019). "Olfactory loss and dysfunction in ciliopathies: Molecular mechanisms and potential therapies". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 26 (17): 3103–3119. doi:10.2174/0929867325666180105102447. ISSN 0929-8673. PMC 6034980. PMID 29303074.

- ↑ Ul Hassan A, Hassan G, Khan SH, Rasool Z, Abida A (January 2009). "Ciliopathy with special emphasis on kartageners syndrome". International Journal of Health Sciences. 3 (1): 65–9. PMC 3068795. PMID 21475513.

- ↑ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) – Symptoms". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 13 May 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ↑ Sadock, Benjamin J.; Sadock, Virginia A. (2008). "7. Delirium, dementia, and amnestic and other cognitive disorders and mental disorders". Kaplan & Sadock's Concise Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry (3rd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-7817-8746-8. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- ↑ Doty RL, Yousem DM, Pham LT, Kreshak AA, Geckle R, Lee WW (September 1997). "Olfactory dysfunction in patients with head trauma". Archives of Neurology. 54 (9): 1131–40. doi:10.1001/archneur.1997.00550210061014. PMID 9311357.

- ↑ Doty RL, Shaman P, Applebaum SL, Giberson R, Siksorski L, Rosenberg L (December 1984). "Smell identification ability: changes with age". Science. 226 (4681): 1441–3. Bibcode:1984Sci...226.1441D. doi:10.1126/science.6505700. PMID 6505700.

- ↑ Seo BS, Lee HJ, Mo JH, Lee CH, Rhee CS, Kim JW (October 2009). "Treatment of postviral olfactory loss with glucocorticoids, Ginkgo biloba, and mometasone nasal spray". Archives of Otolaryngology--Head & Neck Surgery. 135 (10): 1000–4. doi:10.1001/archoto.2009.141. PMID 19841338.

- Lay summary in: "Study Examines Treatment For Olfactory Loss After Viral Infection". ScienceDaily. October 19, 2009.

- ↑ Rupp CI, Fleischhacker WW, Kemmler G, Kremser C, Bilder RM, Mechtcheriakov S, et al. (May 2005). "Olfactory functions and volumetric measures of orbitofrontal and limbic regions in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research. 74 (2–3): 149–61. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.07.010. PMID 15721995. S2CID 11026266.

- ↑ Kieff DA, Boey H, Schaefer PW, Goodman M, Joseph MP (December 1997). "Isolated neurosarcoidosis presenting as anosmia and visual changes". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 117 (6): S183-6. doi:10.1016/S0194-5998(97)70097-4. PMID 9419143.

- ↑ Wheeler TT, Alberts MA, Dolan TA, McGorray SP (December 1995). "Dental, visual, auditory and olfactory complications in Paget's disease of bone". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 43 (12): 1384–91. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06618.x. PMID 7490390. S2CID 26893932.

- ↑ Eriksen KD, Bøge-Rasmussen T, Kruse-Larsen C (June 1990). "Anosmia following operation for cerebral aneurysms in the anterior circulation". Journal of Neurosurgery. 72 (6): 864–5. doi:10.3171/jns.1990.72.6.0864. PMID 2338570.

- ↑ "Anosmia / Loss Of Smell". Archived from the original on 2016-11-12. Retrieved 2011-11-19.[unreliable medical source?]

- ↑ Holbrook EH, Leopold DA (February 2003). "Anosmia: diagnosis and management". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 11 (1): 54–60. doi:10.1097/00020840-200302000-00012. PMID 14515104. S2CID 35835436.

- ↑ Vowles RH, Bleach NR, Rowe-Jones JM (August 1997). "Congenital anosmia". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 41 (2): 207–14. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(97)00075-X. PMID 9306177.

- ↑ Sumner, D (1971). "Appetite and Anosmia". The Lancet. 297 (7706): 970. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(71)91470-X.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Knight, A. (27 August 1988). "Anosmia". The Lancet. 2 (8609): 512. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90160-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 2900434. S2CID 208793859. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.(subscription required)

- ↑ Turnley WH (April 1963). "Anosmia". The Laryngoscope. 73 (4): 468–73. doi:10.1288/00005537-196304000-00012. PMID 13994924. S2CID 221921289.

- ↑ McClay JE (May 1, 2014). "Nasal Polyps Treatment & Management". Medscape. Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ McIntyre JC, Davis EE, Joiner A, Williams CL, Tsai IC, Jenkins PM, et al. (September 2012). "Gene therapy rescues cilia defects and restores olfactory function in a mammalian ciliopathy model". Nature Medicine. 18 (9): 1423–8. doi:10.1038/nm.2860. PMC 3645984. PMID 22941275.

- ↑ Gallagher J (September 3, 2012). "Gene therapy restores sense of smell in mice". BBC News. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ↑ Hoffman HJ, Rawal S, Li CM, Duffy VB (June 2016). "New chemosensory component in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): first-year results for measured olfactory dysfunction". Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders. 17 (2): 221–40. doi:10.1007/s11154-016-9364-1. PMC 5033684. PMID 27287364.

- ↑ Keane, James R.; Baloh, Robert W. (2006). "6. Post traumatic cranial neuropathies". In Randolph W. Evans (ed.). Neurology and Trauma. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-19-517032-0. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- ↑ Walker A, Hopkins C, Surda P (July 2020). "Use of Google Trends to investigate loss-of-smell-related searches during the COVID-19 outbreak". International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology. 10 (7): 839–847. doi:10.1002/alr.22580. PMC 7262261. PMID 32279437.

- ↑ Cooper KW, Brann DH, Farruggia MC, Bhutani S, Pellegrino R, Tsukahara T, et al. (July 2020). "COVID-19 and the Chemical Senses: Supporting Players Take Center Stage". Neuron. 107 (2): 219–233. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.032. PMC 7328585. PMID 32640192.

- ↑ Iravani B, Arshamian A, Ravia A, Mishor E, Snitz K, Shushan S, et al. (11 May 2020). "Relationship between odor intensity estimates and COVID-19 population prediction in a Swedish sample". MedRxiv: 2020.05.07.20094516. doi:10.1101/2020.05.07.20094516. S2CID 218580260.

- ↑ Rodriguez S, Cao L, Rickenbacher GT, Benz EG, Magdamo C, Ramirez Gomez LA, et al. (June 2020). "Innate immune signaling in the olfactory epithelium reduces odorant receptor levels: modeling transient smell loss in COVID-19 patients". MedRxiv: 2020.06.14.20131128. doi:10.1101/2020.06.14.20131128. PMC 7310652. PMID 32587994.

- ↑ "Global Consortium for Chemosensory Research". Global Consortium for Chemosensory Research (GCCR). Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 errors: empty unknown parameters

- All articles lacking reliable references

- Articles lacking reliable references from June 2014

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Pages containing links to subscription-only content

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2017

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Neurological disorders

- Olfactory system

- RTT