Allergic conjunctivitis

| Allergic eye disease | |

|---|---|

| |

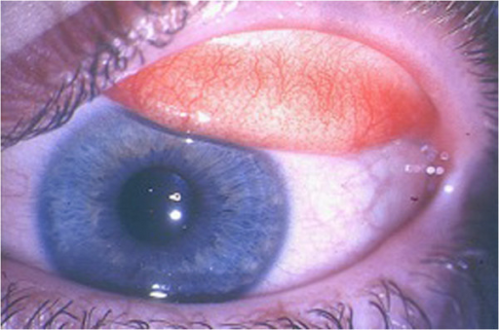

| Illustration of allergic conjunctivitis | |

Allergic conjunctivitis (AC) is inflammation of the conjunctiva (the membrane covering the white part of the eye) due to allergy.[1] Although allergens differ among patients, the most common cause is hay fever. Symptoms consist of redness (mainly due to vasodilation of the peripheral small blood vessels), edema (swelling) of the conjunctiva, itching, and increased lacrimation (production of tears). If this is combined with rhinitis, the condition is termed allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (ARC).

The symptoms are due to release of histamine and other active substances by mast cells, which stimulate dilation of blood vessels, irritate nerve endings, and increase secretion of tears.

Treatment of allergic conjunctivitis is by avoiding the allergen (e.g., avoiding grass in bloom during "hay fever season") and treatment with antihistamines, either topical (in the form of eye drops), or systemic (in the form of tablets). Antihistamines, medications that stabilize mast cells, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are generally safe and usually effective.[2]

Signs and symptoms

The conjunctiva is a thin membrane that covers the eye. When an allergen irritates the conjunctiva, common symptoms that occur in the eye include: ocular itching, eyelid swelling, tearing, photophobia, watery discharge, and foreign body sensation (with pain).[1][3]

Itching is the most typical symptom of ocular allergy, and more than 75% of patients report this symptom when seeking treatment.[3] Symptoms are usually worse for patients when the weather is warm and dry, whereas cooler weather with lower temperatures and rain tend to assuage symptoms.[1] Signs in phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis include small yellow nodules that develop over the cornea, which ulcerate after a few days.[4]

A study by Klein et al. showed that in addition to the physical discomfort allergic conjunctivitis causes, it also alters patients' routines, with patients limiting certain activities such as going outdoors, reading, sleeping, and driving.[3] Therefore, treating patients with allergic conjunctivitis may improve their everyday quality of life.

Causes

The cause of allergic conjunctivitis is an allergic reaction of the body's immune system to an allergen. Allergic conjunctivitis is common in people who have other signs of allergic disease such as hay fever, asthma and eczema.[citation needed]

Among the most common allergens that cause conjunctivitis are:[5]

- Pollen from trees, grass and ragweed

- Animal skin and secretions such as saliva

- Perfumes

- Cosmetics

- Skin medicines

- Air pollution

- Smoke

- Dust mites

- Balsam of Peru (used in food and drink for flavoring, in perfumes and toiletries for fragrance, and in medicine and pharmaceutical items for healing properties)

- Eye drops (A reaction to preservatives in eye drops can cause toxic conjunctivitis)

- Contact lens solution (some preservatives can irritate the eye over time resulting in conjunctivitis)

- Contact lens (conjunctivitis is also caused by repeated mechanical irritation of the conjunctiva by contact lens wearers)

Most cases of seasonal conjunctivitis are due to pollen and occur in the hay fever season, grass pollens in early summer and various other pollens and moulds may cause symptoms later in the summer.[6]

Pathophysiology

The ocular allergic response is a cascade of events that is coordinated by mast cells.[7] Beta chemokines such as eotaxin and MIP-1 alpha have been implicated in the priming and activation of mast cells in the ocular surface. When a particular allergen is present, sensitization takes place and prepares the system to launch an antigen specific response. TH2 differentiated T cells release cytokines, which promote the production of antigen specific immunoglobulin E (IgE). IgE then binds to IgE receptors on the surface of mast cells. Then, mast cells release histamine, which then leads to the release of cytokines, prostaglandins, and platelet-activating factor. Mast cell intermediaries cause an allergic inflammation and symptoms through the activation of inflammatory cells.[3]

When histamine is released from mast cells, it binds to H1 receptors on nerve endings and causes the ocular symptom of itching. Histamine also binds to H1 and H2 receptors of the conjunctival vasculature and causes vasodilatation. Mast cell-derived cytokines such as chemokine interleukin IL-8 are involved in recruitment of neutrophils. TH2 cytokines such as IL-5 recruit eosinophils and IL-4, IL-6, and IL-13, which promote increased sensitivity. Immediate symptoms are due to the molecular cascade. Encountering the allergen a patient is sensitive to leads to increased sensitization of the system and more powerful reactions. Advanced cases can progress to a state of chronic allergic inflammation.[3]

Diagnosis

-

Seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis: mild conjunctival injection and moderate chemosis.

-

Eye with mild allergic conjunctivitis

Classification

SAC and PAC

Both seasonal allergic conjunctivitis (SAC) and perennial allergic conjunctivitis (PAC) are two acute allergic conjunctival disorders.[2] SAC is the most common ocular allergy.[1][8] Symptoms of the aforementioned ocular diseases include itching and pink to reddish eye(s).[2] These two eye conditions are mediated by mast cells.[2][8] Nonspecific measures to ameliorate symptoms include cold compresses, eyewashes with tear substitutes, and avoidance of allergens.[2] Treatment consists of antihistamine, mast cell stabilizers, dual mechanism anti-allergen agents, or topical antihistamines.[2] Corticosteroids are another option, but, considering the side-effects of cataracts and increased intraocular pressure, corticosteroids are reserved for more severe forms of allergic conjunctivitis such as vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) and atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC).[2]

VKC and AKC

Both vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) and atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) are chronic allergic diseases wherein eosinophils, conjunctival fibroblasts, epithelial cells, mast cells, and TH2 lymphocytes aggravate the biochemistry and histology of the conjunctiva.[2] VKC is a disease of childhood and is prevalent in males living in warm climates.[2] AKC is frequently observed in males between the ages of 30 and 50.[2] VKC and AKC can be treated by medications used to combat allergic conjunctivitis or the use of steroids.[2] Maxwell-Lyons sign, shield ulcer, cobblestones papillae, gelatinous thickening at the limbus, and Horner-Trantas dots are specific features of vernal type.[citation needed]

Giant papillary conjunctivitis

Giant papillary conjunctivitis is not a true ocular allergic reaction and is caused by repeated mechanical irritation of the conjunctiva.[2] Repeated contact with the conjunctival surface caused by the use of contact lenses is associated with GPC.[8]

PKC

Phlyctenular keratoconjunctiviti (PKC) results from a delayed hypersensitivity/inflammatory reaction to antigens expressed by various pathogens. Common agents include Staph. aureus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Chlamydia and Candida.[9]

Management

A detailed history allows doctors to determine whether the presenting symptoms are due to an allergen or another source. Diagnostic tests such as conjunctival scrapings to look for eosinophils are helpful in determining the cause of the allergic response.[2] Antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers or dual activity drugs are safe and usually effective.[2] Corticosteroids are reserved for more severe cases of inflammation, and their use should be monitored by an optometrist due to possible side-effects.[2] When an allergen is identified, the person should avoid the allergen as much as possible.[8]

Non-pharmacological methods

If the allergen is encountered and the symptoms are mild, a cold compress or artificial tears can be used to provide relief.[citation needed]

Mast cell stabilizers

Mast cell stabilizers can help people with allergic conjunctivitis. They tend to have delayed results, but they have fewer side-effects than the other treatments and last much longer than those of antihistamines. Some people are given an antihistamine at the same time so that there is some relief of symptoms before the mast cell stabilizers becomes effective. Doctors commonly prescribe lodoxamide and nedocromil as mast cell stabilizers, which come as eye drops.[citation needed]

A mast cell stabilizer is a class of non-steroid controller medicine that reduces the release of inflammation-causing chemicals from mast cells. They block a calcium channel essential for mast cell degranulation, stabilizing the cell, thus preventing the release of histamine. Decongestants may also be prescribed. Another common mast cell stabilizer that is used for treating allergic conjunctivitis is sodium cromoglicate.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines such as diphenhydramine and chlorpheniramine are commonly used as treatment. People treated with H1 antihistamines exhibit reduced production of histamine and leukotrienes as well as downregulation of adhesion molecule expression on the vasculature which in turn attenuates allergic symptoms by 40–50%.[10]

Dual Activity Agents

Dual-action medications are both mast cell stabilizers and antihistamines. They are the most common prescribed class of topical anti allergy agent. Olopatadine (Patanol, Pazeo)[11] and ketotifen fumarate (Alaway or Zaditor)[12] are both commonly prescribed. Ketotifen is available without a prescription in some countries.

Corticosteroids

Ester based "soft" steroids such as loteprednol (Alrex) are typically sufficient to calm inflammation due to allergies, and carry a much lower risk of adverse reactions than amide based steroids.

A systematic review of 30 trials, with 17 different treatment comparisons found that all topical antihistamines and mast cell stabilizers included for comparison were effective in reducing symptoms of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis.[13] There was not enough evidence to determine differences in long-term efficacy among the treatments.[13]

Many of the eye drops can cause burning and stinging, and have side-effects. Proper eye hygiene can improve symptoms, especially with contact lenses. Avoiding precipitants, such as pollen or mold can be preventative.[citation needed]

Immunotherapy

Allergen immunotherapy (AIT) treatment involves administering doses of allergens to accustom the body to substances that are generally harmless (pollen, house dust mites), thereby inducing specific long-term tolerance.[14] Allergy immunotherapy can be administered orally (as sublingual tablets or sublingual drops), or by injections under the skin (subcutaneous). Discovered by Leonard Noon and John Freeman in 1911, allergy immunotherapy represents the only causative treatment for respiratory allergies.

Experimental research has targeted adhesion molecules known as selectins on epithelial cells. These molecules initiate the early capturing and margination of leukocytes from circulation. Selectin antagonists have been examined in preclinical studies, including cutaneous inflammation, allergy and ischemia-reperfusion injury. There are four classes of selectin blocking agents: (i) carbohydrate based inhibitors targeting all P-, E-, and L-selectins, (ii) antihuman selectin antibodies, (iii) a recombinant truncated form of PSGL-1 immunoglobulin fusion protein, and (iv) small-molecule inhibitors of selectins. Most selectin blockers have failed phase II/III clinical trials, or the studies were ceased due to their unfavorable pharmacokinetics or prohibitive cost.[10] Sphingolipids, present in yeast like Saccharomyces cerevisiae and plants, have also shown mitigative effects in animal models of gene knockout mice.[10]

Epidemiology

Allergic conjunctivitis occurs more frequently among those with allergic conditions, with the symptoms having a seasonal correlation.

Allergic conjunctivitis is a frequent condition as it is estimated to affect 20 percent of the population on an annual basis and approximately one-half of these people have a personal or family history of atopy.[citation needed]

Giant papillary conjunctivitis accounts for 0.5–1.0% of eye disease in most countries.[citation needed]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Bielory L, Friedlaender MH (February 2008). "Allergic conjunctivitis". Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 28 (1): 43–58, vi. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2007.12.005. PMID 18282545.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Ono SJ, Abelson MB (January 2005). "Allergic conjunctivitis: update on pathophysiology and prospects for future treatment". J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 115 (1): 118–22. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.042. PMID 15637556.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Whitcup SM (2006). Cunningham ET Jr; Ng EWM (eds.). "Recent advances in ocular therapeutics". Int Ophthalmol Clin. 46 (4): 1–6. doi:10.1097/01.iio.0000212140.70051.33. PMID 17060786. S2CID 32853661.

- ↑ Onofrey, Bruce E.; Skorin, Leonid; Holdeman, Nicky R. (2005-01-01). Ocular Therapeutics Handbook: A Clinical Manual. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781748926. Archived from the original on 2021-07-10. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

... including virus, fungus, chlamydia, and nematodes.

- ↑ Karakus, S. "Allergic Conjunctivitis". Johns Hopkins Medicine. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ↑ "What is conjunctivitis?". patient.info. Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ↑ Liu G, Keane-Myers A, Miyazaki D, Tai A, Ono SJ (1999). "Molecular and cellular aspects of allergic conjunctivitis". Immune Response and the Eye. Chem. Immunol. Chemical Immunology and Allergy. Vol. 73. pp. 39–58. doi:10.1159/000058748. ISBN 978-3-8055-6893-7. PMID 10590573.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Buckley RJ (December 1998). "Allergic eye disease—a clinical challenge". Clin. Exp. Allergy. 28 (Suppl 6): 39–43. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.0280s6039.x. PMID 9988434. S2CID 23496108.

- ↑ Allansmith M.R.; Ross R.N. (1991). "Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis". In Tasman W.; Jaeger E.A. (eds.). Duane's Clinical Ophthalmology. Vol. 1 (revised ed.). Philadelphia: Harper & Row. pp. 1–5.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Sun, W. Y.; Bonder, C. S. (2012). "Sphingolipids: A Potential Molecular Approach to Treat Allergic Inflammation". Journal of Allergy. 2012: 1–14. doi:10.1155/2012/154174. PMC 3536436. PMID 23316248.

- ↑ Rosenwasser LJ, O'Brien T, Weyne J (September 2005). "Mast cell stabilization and anti-histamine effects of olopatadine ophthalmic solution: a review of pre-clinical and clinical research". Curr Med Res Opin. 21 (9): 1377–87. doi:10.1185/030079905X56547. PMID 16197656. S2CID 8954933.

- ↑ Avunduk AM, Tekelioglu Y, Turk A, Akyol N (September 2005). "Comparison of the effects of ketotifen fumarate 0.025% and olopatadine HCl 0.1% ophthalmic solutions in seasonal allergic conjunctivities: a 30-day, randomized, double-masked, artificial tear substitute-controlled trial". Clin Ther. 27 (9): 1392–402. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.09.013. PMID 16291412.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Castillo M, Scott NW, Mustafa MZ, Mustafa MS, Azuara-Blanco A (2015). "Topical antihistamines and mast cell stabilisers for treating seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6 (6): CD009566. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009566.pub2. hdl:2164/6048. PMID 26028608.

- ↑ Van Overtvelt L. et al. Immune mechanisms of allergen-specific sublingual immunotherapy. Revue française d'allergologie et d'immunologie clinique. 2006; 46: 713–720.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Allergic Conjunctivitis at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Pages with script errors

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2014

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2014

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2013

- Disorders of conjunctiva

- Allergology