Acarbose

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Glucobay, Precose, Prandase, others |

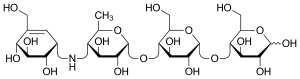

| Other names | (2R,3R,4R,5S,6R)-5-{[(2R,3R,4R,5S,6R)-5- {[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4-dihydroxy-6-methyl- 5-{[(1S,4R,5S,6S)-4,5,6-trihydroxy-3- (hydroxymethyl)cyclohex-2-en-1-yl]amino} tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl]oxy}-3,4-dihydroxy- 6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl]oxy}- 6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2,3,4-triol |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Main uses | Type 2 diabetes[1] |

| Side effects | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, increase bowel gas[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth (tablets) |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a696015 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | Extremely low |

| Metabolism | Gastrointestinal tract |

| Elimination half-life | 2 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney (less than 2%) |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C25H43NO18 |

| Molar mass | 645.608 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Acarbose is a medication used to treat type 2 diabetes, along with diet and exercise.[1] It may be used in those who cannot take metformin or in addition to other diabetes medications.[1] Its benefit is small.[2] It is taken by mouth with each meal.[1] Maximal effect may take 2 weeks.[1]

Common side effects include abdominal pain, diarrhea, and increase bowel gas.[1] When used alone, it does not typically result in low blood sugar.[1] Other side effects include increased liver enzymes.[1] Use is not recommended in those at risk of bowel obstruction.[2] It works by slowing down the digestion of carbohydrates.[1]

Acarbose was approved for medical use in the United States in 1995.[1] It is available as a generic medication.[3] In the United States a month costs about 16 USD as of 2021.[3] In the United Kingdom this amount costs the NHS about 15 pounds.[2]

Medical uses

Its use is limited in the United States because it is not potent enough to justify the side effects of diarrhea and flatulence.[4] However, a recent large study concludes "acarbose is effective, safe and well tolerated in a large cohort of Asian patients with type 2 diabetes."[5] A possible explanation for the differing opinions is an observation that acarbose is significantly more effective in patients eating a relatively high carbohydrate Eastern diet.[6]

Dosing

Since acarbose prevents the digestion of complex carbohydrates, the drug should be taken at the start of main meals (taken with first bite of meal). Moreover, the amount of complex carbohydrates in the meal will determine the effectiveness of acarbose in decreasing postprandial hyperglycemia. Adults may take doses of 25 mg 3 times daily, increasing to 100 mg 3 times a day.[1] The maximum dose per day is 600 mg.[2]

Combination therapy

The combination of acarbose with metformin results in greater reductions of HbA1c, fasting blood glucose and post-prandial glucose than either agent alone.[7]

Side-effects

Since acarbose prevents the degradation of complex carbohydrates into glucose, some carbohydrate will remain in the intestine and be delivered to the colon. In the colon, bacteria digest the complex carbohydrates, causing gastrointestinal side-effects such as flatulence (78% of patients) and diarrhea (14% of patients). Since these effects are dose-related, in general it is advised to start with a low dose and gradually increase the dose to the desired amount. One study found that gastrointestinal side effects decreased significantly (from 50% to 15%) over 24 weeks, even on constant dosing.[8]

If a patient using acarbose suffers from a bout of hypoglycemia, the patient must eat something containing monosaccharides, such as glucose tablets or gel (GlucoBurst, Insta-Glucose, Glutose, Level One) and a doctor should be called. Because acarbose blocks the breakdown of table sugar and other complex sugars, fruit juice or starchy foods will not effectively reverse a hypoglycemic episode in a patient taking acarbose.[9]

Hepatitis has been reported with acarbose use. It usually goes away when the medicine is stopped.[10] Therefore, liver enzymes should be checked before and during use of this medicine.

Mechanism of action

Acarbose inhibits enzymes (glycoside hydrolases) needed to digest carbohydrates, specifically, alpha-glucosidase enzymes in the brush border of the small intestines, and pancreatic alpha-amylase.

Pancreatic alpha-amylase hydrolyzes complex starches to oligosaccharides in the lumen of the small intestine, whereas the membrane-bound intestinal alpha-glucosidases hydrolyze oligosaccharides, trisaccharides, and disaccharides to glucose and other monosaccharides in the small intestine. Inhibition of these enzyme systems reduces the rate of digestion of complex carbohydrates. Less glucose is absorbed because the carbohydrates are not broken down into glucose molecules. In diabetic patients, the short-term effect of these drug therapies is to decrease current blood glucose levels; the long-term effect is a reduction in HbA1c level.[11] This reduction averages an absolute decrease of 0.7%, which is a decrease of about 10% in typical HbA1c values in diabetes studies.[12]

Terminology

It is a generic sold in Europe and China as Glucobay, in North America as Precose, and in Canada as Prandase.

Research

In preliminary research it extend the lifespan of female mice by 5% and of male mice by 22%.[15][16]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 "Acarbose Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 729. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Acarbose Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ↑ Kresge N (21 November 2011). "China's Thirst for New Diabetes Drugs Threatens Bayer's Lead". Bloomberg Business Week. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ Zhang W, Kim D, Philip E, Miyan Z, Barykina I, Schmidt B, Stein H (April 2013). "A multinational, observational study to investigate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of acarbose as add-on or monotherapy in a range of patients: the Gluco VIP study". Clinical Drug Investigation. 33 (4): 263–74. doi:10.1007/s40261-013-0063-3. PMID 23435929. S2CID 207483590.

- ↑ Zhu Q, Tong Y, Wu T, Li J, Tong N (June 2013). "Comparison of the hypoglycemic effect of acarbose monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus consuming an Eastern or Western diet: a systematic meta-analysis". Clinical Therapeutics. 35 (6): 880–99. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.03.020. PMID 23602502.

- ↑ Hedrington MS, Davis SN (2019). "Considerations when using alpha-glucosidase inhibitors in the treatment of type 2 diabetes". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 20 (18): 2229–2235. doi:10.1080/14656566.2019.1672660. PMID 31593486.

- ↑ Hoffmann J, Spengler M (December 1997). "Efficacy of 24-week monotherapy with acarbose, metformin, or placebo in dietary-treated NIDDM patients: the Essen-II Study". The American Journal of Medicine. 103 (6): 483–90. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00252-0. PMID 9428831.

- ↑ "Acarbose". MedlinePlus Drug Information. Archived from the original on 2016-07-05. Retrieved 2018-03-21.

- ↑ "Acarbose: hepatitis: France, Spain". WHO Pharmaceuticals Newsletter. 1999. Archived from the original on 2009-10-15. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ Drug Therapy in Nursing, 2nd Edition.

- ↑ Scheen AJ (September 1998). "Clinical efficacy of acarbose in diabetes mellitus: a critical review of controlled trials". Diabetes & Metabolism. 24 (4): 311–20. PMID 9805641.

- ↑ J. Elks; C. R. Ganellin (1990). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 1–. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-2085-3. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ↑ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances. Recommended International Nonproprietary Names (Rec. INN): List 19" (PDF). World Health Organization. 1979. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ↑ Harrison DE, Strong R, Allison DB, Ames BN, Astle CM, Atamna H, Fernandez E, Flurkey K, Javors MA, Nadon NL, Nelson JF, Pletcher S, Simpkins JW, Smith D, Wilkinson JE, Miller RA (2014). "Acarbose, 17-α-estradiol, and nordihydroguaiaretic acid extend mouse lifespan preferentially in males". Aging Cell. 13 (2): 273–282. doi:10.1111/acel.12170. PMC 3954939. PMID 24245565.

- ↑ Ladiges W, Liggitt D (2017). "Testing drug combinations to slow aging". Pathobiology of Aging & Age-related Diseases. 8 (1): 1407203. doi:10.1080/20010001.2017.1407203. PMC 5706479. PMID 29291036.

External links

- "Acarbose". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-03-18. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- "Probing the Pancreas" - by Craig D. Reid, Ph.D. Archived 2013-06-06 at the Wayback Machine (US FDA Consumer Article)

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: date format

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors

- Amino sugars

- Bayer brands

- Oligosaccharides

- Cyclohexenes

- RTT