Abdominal thrusts

| Abdominal thrusts | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Heimlich maneuver, Heimlich manoeuvre | |

| |

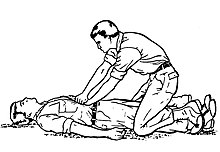

| Performing the Heimlich maneuver | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

| Indications | Severe choking[1] |

| Contraindications | Under 1 year old, pregnant[2] |

| Steps | 1) Stand behind the person and place your arms around their middle[2] 2) Clench a fist at just above the belly button[2] 3) Place the other hand over the fist and pull it in and upwards[2] 4) The prior step may be repeated 5 to 10 times[1][2] |

| Complications | Injury to the ribs, liver, stomach or spleen, vomiting[1][1] |

Abdominal thrusts, also known as the Heimlich maneuver, is a treatment for severe choking (foreign body airway obstruction).[1] Specifically it is used in those over the age of 1 who are unable to cough but remain conscious.[3] It is not recommended in those under 1 year old or who are pregnant.[2] In those under 1 back slaps and chest thrusts are recommended, while in those who are pregnant chest thrusts are used.[3][1]

The rescuer should start standing behind the person.[2] They should than wrap their arms around the person's waist and bend them forwards.[1][2] This is followed by clenching one hand into a fist, just above the belly button, and using the other hand and arms to pull the fist inward and upwards.[2] This final movement may be repeated 5 to 10 times.[1][2] For a child a person may need to kneel.[1]

Complications may include injury to the ribs, liver, stomach or spleen injury.[1] It is possible that vomiting may also occur.[1] If the person becomes unconscious cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be started.[1] Henry Heimlich, an American surgeon, is credited with the procedures creation in 1974.[4]

Medical uses

Abdominal thrusts are a treatment for severe choking (foreign body airway obstruction).[1] Specifically it is used in those over the age of 1 who are unable to cough but remain conscious.[3]

A universal sign of choking in someone who is unable to talk consists of placing both hands on one's own throat while trying to attract the attention of others who might assist.[6]

Contraindications

The procedure should not be done on those under 1 year old or who are pregnant.[2]

Technique

A number of variations have been described. In Europe 5 black slaps followed by 5 abdominal thrusts is recommended.[7] In the United States and the UK 5 to 10 abdominal thrusts are done in a row.[1][2]

Steps include:

- Stand behind the person and place your arms around their middle[2]

- Clench a fist at just above the belly button[2]

- Place the other hand over the fist and pull it in and upwards[2]

- The prior step may be repeated 5 to 10 times[1][2]

The pressure amounts to an artificially induced cough. To assist a larger person, more force may be needed. The Mayo Clinic recommends the same placement of fist and hand and upward thrusts as if you are trying to lift the person.

It is possible for still-conscious people to perform the procedure on themselves, without assistance.[8]

Similar intrathoracic pressures (50–60 cmH2O) are produced when performing abdominal thrusts inwards as are produced when the force is directed inwards and upwards.[9][10] They argue that this may be easier to perform with less concern about injury to ribcage or upper abdominal organs. Self-administered abdominal thrusts by study participants produced similar pressures to those generated by first aiders. The highest pressures were produced by participants performing an abdominal thrust onto the back of a chair (115 cmH2O).

Alternatives

If the person choking should not receive pressures on the abdomen (for example, in case of pregnancy or excessive obesity), chest thrusts are advised instead.[11] These are applied on the lower half of the chest, but not in the very endpoint (which is the xiphoid process). In contrast to the prevailing American and European advice, the Australian Resuscitation Council recommends chest thrusts instead of abdominal thrusts.[12]

If the person choking is not upright, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommends positioning the person on their back, then straddling the torso and using chest thrusts.[13]

Complications

Due to the forceful nature of the procedure, even when done correctly, abdominal thrusts can injure the person on whom it is performed. Bruising to the abdomen is highly likely and more serious injuries can occur, including fracture of the xiphoid process or ribs.[14] Anyone who has been subjected to abdominal thrusts should seek a medical examination afterwards.[15]

History

Jewish-American thoracic surgeon and medical researcher Henry Heimlich, noted for promulgating abdominal thrusts, claimed that back slaps were proven to cause death by lodging foreign objects into the windpipe.[16] The 1982 Yale study by Day, DuBois, and Crelin that persuaded the American Heart Association to stop recommending back blows for dealing with choking was partially funded by Heimlich's own foundation.[17] According to Roger White MD of the Mayo Clinic and American Heart Association (AHA), "There was never any science here. Heimlich overpowered science all along the way with his slick tactics and intimidation, and everyone, including us at the AHA, caved in."[18]

From 1985 to 2005, abdominal thrusts were the only recommended treatment for choking in the published guidelines of the American Heart Association and the American Red Cross. In 2006, both organizations changed course and "downgraded" the use of the technique. For conscious people, the new guidelines recommend first encouraging coughing and than potentially applying back slaps; if this method failed to remove the airway obstruction, rescuers were to then apply abdominal thrusts. For unconscious people, the guidelines recommend chest thrusts.

Henry Heimlich also promoted abdominal thrusts as a treatment for drowning[19] and asthma attacks.[20] The Red Cross now contests those claims. The Heimlich Institute has stopped advocating on their website for the Heimlich maneuver to be used as a first aid measure for drowning victims. His son, Peter M. Heimlich, alleges that in August 1974 his father published the first of a series of fraudulent case reports in order to promote the use of abdominal thrusts for near-drowning rescue.[21][22] The 2005 drowning rescue guidelines of the American Heart Association[23] did not include citations of Heimlich's work, and warned against the use of the Heimlich maneuver for drowning rescue as unproven and dangerous, due to its risk of vomiting leading to aspiration.[23]

In May 2016 Henry Heimlich, age 96, personally used the maneuver to save the life of a fellow resident at his retirement home in Cincinnati. According to the article, it was either the first or second time Heimlich himself used his namesake maneuver to save the life of someone in a non-simulated choking situation.[4]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 "How To Do the Heimlich Maneuver in the Conscious Adult or Child - Critical Care Medicine". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 "What should I do if someone is choking?". nhs.uk. 26 June 2018. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Duckett, Stephanie A.; Bartman, Marc; Roten, Ryan A. (2022). "Choking". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Dr Henry Heimlich uses Heimlich manoeuvre to save a life at 96". the Guardian. 27 May 2016. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ↑ Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Edition 101 MD0532 (PDF). U. S. ARMY MEDICAL DEPARTMENT CENTER AND SCHOOL FORT SAM HOUSTON, TEXAS 78234. p. 5-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ↑ "Choking first aid – adult or child over 1 year – series". MedlinePlus. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on July 28, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ↑ Nolan, JP; Soar, J; Zideman, DA; Biarent, D; Bossaert, LL; Deakin, C; Koster, RW; Wyllie, J; Böttiger, B; ERC Guidelines Writing Group (2010). "European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 1. Executive summary". Resuscitation. 81 (10): 1219–76. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.021. hdl:10067/1302980151162165141. PMID 20956052.

- ↑ "Heimlich maneuver on self". MedlinePlus. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on July 5, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ↑ Pavitt, Matthew J.; Swanton, Laura L.; Hind, Matthew; Apps, Michael; Polkey, Michael I.; Green, Malcolm; Hopkinson, Nicholas S. (April 5, 2017). "Choking on a foreign body: a physiological study of the effectiveness of abdominal thrust manoeuvres to increase thoracic pressure". Thorax. 72 (6): 576–578. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209540. ISSN 0040-6376. PMC 5520267. PMID 28404809.

- ↑ "How to perform the Heimlich manoeuvre on yourself (and yes, it's just as effective)". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Choking Safety Talk". Oklahoma State University. Archived from the original on 2020-01-30.

- ↑ "Australian (and New Zealand) Resuscitation Council Guideline 4 AIRWAY". Australian Resuscitation Council (2010). Archived from the original on February 14, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- ↑ "Abdominal thrusts". MedlinePlus. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on July 5, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ↑ Broomfield, James (January 1, 2007). "Heimlich maneuver on self". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on August 29, 2007. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- ↑ "What should I do if someone is choking? NHS.UK". October 30, 2015. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ↑ "Heimlich, on the maneuver". The New York Times. February 6, 2009. Archived from the original on September 18, 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Lifejackets on Ice (August 2005)" (PDF). University of Pittsburgh Medical School. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2009.

- ↑ Pamela Mills-Senn (April 2007). "A New Maneuver (August 2005)". Cincinnati Magazine. Archived from the original on November 15, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Heimlich Institute on rescuing drowning victims". Archived from the original on January 24, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Heimlich Institute on rescuing asthma victims". Archived from the original on March 14, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ↑ Heimlich, Peter M. "Outmaneuvered – How We Busted the Heimlich Medical Frauds". Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ Heimlich's son cites Dallas case in dispute. Archived 2017-10-17 at the Wayback Machine Wilkes-Barre News, August 22, 2007

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Part 10.3: Drowning". Circulation. 112 (24): 133–135. November 25, 2005. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166565. Archived from the original on April 4, 2008. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

External links

| The Wikibook First Aid has a page on the topic of: Obstructed Airway |