ACSL4

Long-chain-fatty-acid—CoA ligase 4 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ACSL4 gene.[5][6][7]

The protein encoded by this gene is an isozyme of the long-chain fatty-acid-coenzyme A ligase family. Although differing in substrate specificity, subcellular localization, and tissue distribution, all isozymes of this family convert free long-chain fatty acids into fatty acyl-CoA esters, and thereby play a key role in lipid biosynthesis and fatty acid degradation. This isozyme preferentially utilizes arachidonate as substrate. The absence of this enzyme may contribute to the intellectual disability or Alport syndrome. Alternative splicing of this gene generates 2 transcript variants.[7]

Structure

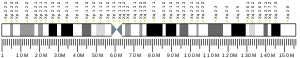

The ACSL4 gene is located on the X-chromosome, with its specific location being Xq22.3-q23. The gene contains 17 exons.[7] ASCL4 encodes a 74.4 kDa protein, FACL4, which is composed of 670 amino acids; 17 peptides have been observed through mass spectrometry data.[8][9]

Function

Fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 (FACL4), the protein encoded by the ACSL4 gene, is an acyl-CoA synthetase, which is an essential class of lipid metabolism enzymes, and ACSL4 is distinguished by its preference for arachidonic acid.[10] The enzyme controls the level of this fatty acid in cells; because AA is known to induce apoptosis (cell specific), the enzyme modulates apoptosis.[11] Overexpression of ACSL4 results in a higher rate of arachidonoyl-CoA synthesis, increased 20:4 incorporation into phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylinositol, and triacylglycerol, and reduced cellular levels of unesterified 20:4. Additionally, ACSL4 regulates PGE2 release from human smooth muscle cells. ACSL4 may regulate a number of processes dependent on the release of arachidonic acid-derived lipid mediators in the arterial wall.[12]

Clinical significance

The most common SNP (C to T substitution) in the first intron of the FACL4 gene is associated with altered FA composition of plasma phosphatidylcholines in patients with Metabolic Syndrome.[13] It has been implicated in many mechanisms of carcinogenesis and neuronal development.[10]

Cancer

In breast cancer, ACSL4 can serve as both a biomarker for and mediator of an aggressive breast cancer phenotype. ACSL4 also is positively correlated with a unique subtype of triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), which is characterized by the absence of androgen receptor (AR) and therefore referred to as quadruple negative breast cancer (QNBC).[14]

The encoded protein FACL4 also plays a role in the growth of hepatic cancer cells. Inhibiting FACL4 leads to inhibition of human liver tumor cells, as marked by an increased level of apoptosis.[15] It has also been suggested that modulation of FACL4 expression/activity is an approach for treatment of hepatic cell carcinoma (HCC).[11]

The FACL4 pathway is also important in colon carcinogenesis; the development of selective inhibitors for FACL4 may be a worthy effort in the prevention and treatment of colon cancer. FACL4 up-regulation appears to occur during the transformation from the cancer from adenoma to adenocarcinoma. Additionally, some colon tumor promoters significantly induced FACL4 expression.[16]

Neuronal development

FACL4 was the gene shown to be involved in nonspecific intellectual disability and fatty-acid metabolism.[17] Since the ASCL4 gene is highly expressed in brain, where it encodes a brain specific isoform, a FACL4 mutation may be an efficient diagnostic tool in intellectually disabled males.[18] FACL4was discovered to bedeleted in a family with Alport syndrome and elliptocytosis.[19]

Interactions

ACSL4 expression is regulated by SHP2 activity.[20] Additionally, ACSL4 interacts with ACSL3, APP, DSE, ELAVL1, HECW2, MINOS1, PARK2, SPG20, SUMO2, TP53, TUBGCP3, UBC, UBD, and YWHAQ.[7]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000068366 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000031278 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Piccini M, Vitelli F, Bruttini M, Pober BR, Jonsson JJ, Villanova M, Zollo M, Borsani G, Ballabio A, Renieri A (Apr 1998). "FACL4, a new gene encoding long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4, is deleted in a family with Alport syndrome, elliptocytosis, and mental retardation". Genomics. 47 (3): 350–8. doi:10.1006/geno.1997.5104. PMID 9480748.

- ^ Verot L, Alloisio N, Morle L, Bozon M, Touraine R, Plauchu H, Edery P (Sep 2003). "Localization of a non-syndromic X-linked mental retardation gene (MRX80) to Xq22-q24". Am J Med Genet A. 122A (1): 37–41. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.20221. PMID 12949969. S2CID 31041475.

- ^ a b c d "Entrez Gene: ACSL4 acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4".

- ^ Zong NC, Li H, Li H, Lam MP, Jimenez RC, Kim CS, Deng N, Kim AK, Choi JH, Zelaya I, Liem D, Meyer D, Odeberg J, Fang C, Lu HJ, Xu T, Weiss J, Duan H, Uhlen M, Yates JR, Apweiler R, Ge J, Hermjakob H, Ping P (Oct 2013). "Integration of cardiac proteome biology and medicine by a specialized knowledgebase". Circulation Research. 113 (9): 1043–53. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301151. PMC 4076475. PMID 23965338.

- ^ "Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4". Cardiac Organellar Protein Atlas Knowledgebase (COPaKB). Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ a b Küch, EM; Vellaramkalayil, R; Zhang, I; Lehnen, D; Brügger, B; Sreemmel, W; Ehehalt, R; Poppelreuther, M; Füllekrug, J (February 2014). "Differentially localized acyl-CoA synthetase 4 isoenzymes mediate the metabolic channeling of fatty acids towards phosphatidylinositol". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1841 (2): 227–39. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.10.018. PMID 24201376.

- ^ a b Sung, YK; Park, MK; Hong, SH; Hwang, SY; Kwack, MH; Kim, JC; Kim, MK (31 August 2007). "Regulation of cell growth by fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells". Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 39 (4): 477–82. doi:10.1038/emm.2007.52. PMID 17934335.

- ^ Golej, DL; Askari, B; Kramer, F; Barnhart, S; Vivekanandan-Giri, A; Pennathur, S; Bornfeldt, KE (April 2011). "Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4 modulates prostaglandin E2 release from human arterial smooth muscle cells". Journal of Lipid Research. 52 (4): 782–93. doi:10.1194/jlr.m013292. PMC 3053208. PMID 21242590.

- ^ Zeman, M; Vecka, M; Jáchymová, M; Jirák, R; Tvrzická, E; Stanková, B; Zák, A (April 2009). "Fatty acid CoA ligase-4 gene polymorphism influences fatty acid metabolism in metabolic syndrome, but not in depression". The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine. 217 (4): 287–93. doi:10.1620/tjem.217.287. PMID 19346733.

- ^ Wu, X; Li, Y; Wang, J; Wen, X; Marcus, MT; Daniels, G; Zhang, DY; Ye, F; Wang, LH; Du, X; Adams, S; Singh, B; Zavadil, J; Lee, P; Monaco, ME (2013). "Long chain fatty Acyl-CoA synthetase 4 is a biomarker for and mediator of hormone resistance in human breast cancer". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e77060. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...877060W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077060. PMC 3796543. PMID 24155918.

- ^ Hu, C; Chen, L; Jiang, Y; Li, Y; Wang, S (January 2008). "The effect of fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 on the growth of hepatic cancer cells". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 7 (1): 131–4. doi:10.4161/cbt.7.1.5198. PMID 18059177.

- ^ Cao, Y; Dave, KB; Doan, TP; Prescott, SM (1 December 2001). "Fatty acid CoA ligase 4 is up-regulated in colon adenocarcinoma". Cancer Research. 61 (23): 8429–34. PMID 11731423.

- ^ Meloni, I; Muscettola, M; Raynaud, M; Longo, I; Bruttini, M; Moizard, MP; Gomot, M; Chelly, J; des Portes, V; Fryns, JP; Ropers, HH; Magi, B; Bellan, C; Volpi, N; Yntema, HG; Lewis, SE; Schaffer, JE; Renieri, A (April 2002). "FACL4, encoding fatty acid-CoA ligase 4, is mutated in nonspecific X-linked mental retardation". Nature Genetics. 30 (4): 436–40. doi:10.1038/ng857. PMID 11889465. S2CID 23901437.

- ^ Longo, I; Frints, SG; Fryns, JP; Meloni, I; Pescucci, C; Ariani, F; Borghgraef, M; Raynaud, M; Marynen, P; Schwartz, C; Renieri, A; Froyen, G (January 2003). "A third MRX family (MRX68) is the result of mutation in the long chain fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 (FACL4) gene: proposal of a rapid enzymatic assay for screening mentally retarded patients". Journal of Medical Genetics. 40 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1136/jmg.40.1.11. PMC 1735250. PMID 12525535.

- ^ Piccini, M; Vitelli, F; Bruttini, M; Pober, BR; Jonsson, JJ; Villanova, M; Zollo, M; Borsani, G; Ballabio, A; Renieri, A (1 February 1998). "FACL4, a new gene encoding long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4, is deleted in a family with Alport syndrome, elliptocytosis, and mental retardation". Genomics. 47 (3): 350–8. doi:10.1006/geno.1997.5104. PMID 9480748.

- ^ Cooke, M; Orlando, U; Maloberti, P; Podestá, EJ; Cornejo Maciel, F (November 2011). "Tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 regulates the expression of acyl-CoA synthetase ACSL4". Journal of Lipid Research. 52 (11): 1936–48. doi:10.1194/jlr.m015552. PMC 3196225. PMID 21903867.

Further reading

- Knights KM, Jones ME (1992). "Inhibition kinetics of hepatic microsomal long chain fatty acid-CoA ligase by 2-arylpropionic acid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs". Biochem. Pharmacol. 43 (7): 1465–71. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(92)90203-U. PMID 1567471.

- Cao Y, Traer E, Zimmerman GA, et al. (1998). "Cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of human long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 (FACL4)". Genomics. 49 (2): 327–30. doi:10.1006/geno.1998.5268. PMID 9598324.

- Jonsson JJ, Renieri A, Gallagher PG, et al. (1998). "Alport syndrome, mental retardation, midface hypoplasia, and elliptocytosis: a new X linked contiguous gene deletion syndrome?". J. Med. Genet. 35 (4): 273–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.35.4.273. PMC 1051272. PMID 9598718.

- Knights KM, Gasser R, Klemisch W (2000). "In vitro metabolism of acitretin by human liver microsomes: evidence of an acitretinoyl-coenzyme A thioester conjugate in the transesterification to etretinate". Biochem. Pharmacol. 60 (4): 507–16. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(00)00339-7. PMID 10874125.

- Cao Y, Dave KB, Doan TP, Prescott SM (2002). "Fatty acid CoA ligase 4 is up-regulated in colon adenocarcinoma". Cancer Res. 61 (23): 8429–34. PMID 11731423.

- Meloni I, Muscettola M, Raynaud M, et al. (2002). "FACL4, encoding fatty acid-CoA ligase 4, is mutated in nonspecific X-linked mental retardation". Nat. Genet. 30 (4): 436–40. doi:10.1038/ng857. PMID 11889465. S2CID 23901437.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. (2003). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916899M. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Longo I, Frints SG, Fryns JP, et al. (2003). "A third MRX family (MRX68) is the result of mutation in the long chain fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 (FACL4) gene: proposal of a rapid enzymatic assay for screening mentally retarded patients". J. Med. Genet. 40 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1136/jmg.40.1.11. PMC 1735250. PMID 12525535.

- Sung YK, Hwang SY, Park MK, et al. (2003). "Fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 is overexpressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma". Cancer Sci. 94 (5): 421–4. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01458.x. PMID 12824887. S2CID 7377512.

- Mashek DG, Bornfeldt KE, Coleman RA, et al. (2005). "Revised nomenclature for the mammalian long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase gene family". J. Lipid Res. 45 (10): 1958–61. doi:10.1194/jlr.E400002-JLR200. PMID 15292367.

- Gerhard DS, Wagner L, Feingold EA, et al. (2004). "The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA project: the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC)". Genome Res. 14 (10B): 2121–7. doi:10.1101/gr.2596504. PMC 528928. PMID 15489334.

- Liang YC, Wu CH, Chu JS, et al. (2005). "Involvement of fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 in hepatocellular carcinoma growth: roles of cyclic AMP and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase". World J. Gastroenterol. 11 (17): 2557–63. doi:10.3748/wjg.v11.i17.2557. PMC 4305743. PMID 15849811.

- Bhat SS, Schmidt KR, Ladd S, et al. (2006). "Disruption of DMD and deletion of ACSL4 causing developmental delay, hypotonia, and multiple congenital anomalies". Cytogenet. Genome Res. 112 (1–2): 170–5. doi:10.1159/000087531. PMID 16276108. S2CID 24779372.

- Sung YK, Park MK, Hong SH, et al. (2007). "Regulation of cell growth by fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells". Exp. Mol. Med. 39 (4): 477–82. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.540.7420. doi:10.1038/emm.2007.52. PMID 17934335. S2CID 17751379.

External links

- Human ACSL4 genome location and ACSL4 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.